Two favorite games of mine from 2024 are against type being narratively driven with 1000XResist and Mouthwashing. Both from indie developers, both very dark and mature, and both using videogames to tell and depict a story differently from everything else. Videogame narratives have seen a growth over the 2010’s, and it’s been awhile since I’ve sat down to think about how this has played out for developers.

The Player is In Control

Videogames are unique among every other medium for storytelling for one very simple and obvious point — videogames are interactive. It’s this level of interactivity that leads to a lot more serious topics about depiction and intent in games. When we’re watching a movie or TV show, the intent and behavior of the person(s) on screen are out of our control; we are of course a passive observer. In a videogame, even the most simplistic ones, the player is the force pushing things forward. If they don’t want to do it, it’s as simple as hitting “quit game”.

Part of the evolution of storytelling has been moving away from simple character motivations — you’re the good guy, you need to save the princess, you win. We first saw this break in the 2000’s with games trying to give the player more agency in the form of morality choices, but this always rang hollow given the fact that the story is still out of the player’s control. It doesn’t matter how good or evil you are, the endings are predetermined, you’re just choosing whether you go through door A or door B.

Instead, narratives became more interesting from indie developers by laying into the fact that someone is playing a game, and using the mechanics and structure of a game to either surprise them or fit the storytelling. Horror has seen a huge bump in this style, by presenting genres and mechanics not typical from the horror genre, and building entire games and franchises out of it.

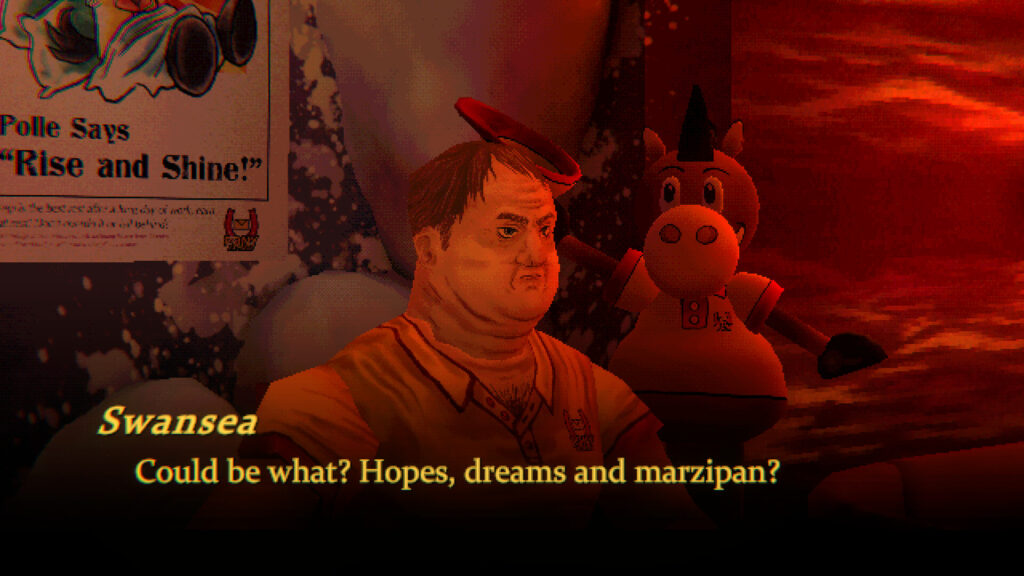

The beauty of screenshots for both games is that none of it will mean anything unless you’ve already played them. (source: Steam)

One of the first well-known examples of unique horror using game logic would be something like Pony Island, and how it used videogames as the actual storytelling medium to keep the player on their toes and pull the rug out from under them.

However, many games fall into the stereotype of a “walking sim”, in that the space, and the mechanics themselves are simply window dressing for telling a story that could just have been done as a movie. But games that do this right, like 1000X Resist and Mouthwashing know that they are videogames, and that they want to bring the player into whatever uncomfortable situation that is going on.

The Slow-Moving (and Running) Car Crash

Both games are not about high interactivity or mechanics for the player to engage with. While there are scenes that the player can fail, there is no penalty, and they can instantly retry these sections. Instead, what these games do well is use the language of games and interactivity in very different ways to bring the player along for the ride.

In 1000X Resist, the player is in control of “Watcher” a clone created by the sole remaining human on the planet who is now known as AllMother. Her responsibility is to go through the memories of the AllMother to learn about her past and what became of the entire world. This is accomplished by manually choosing when to move between memories and it gives the player all the time in the world to soak in what’s going on… or be the one who gets to make things unravel. There is a part that occurs early on involving one of the memories when you know that it’s going to go badly, but you have no choice but to push things forward and see when things go to hell. The game reminds me a lot of Return of the Obra Dinn and how there is this voyeurism to the events — everything has already happened: you’re not there to save the day or right a wrong, but to bear witness to how things really unfolded.

Mouthwashing, on the other hand does something very special with its storytelling and to say it means spoiling the twist.

WARNING: DO NOT READ THE FOLLOWING IF YOU HAVE ANY INTENT ON PLAYING MOUTHWASHING, SKIP TO THE NEXT PARAGRAPH IF YOU DON’T WANT TO BE SPOILED.

5

4

3

2

1

The game gives us a false pretense at the start, saying that Curly, the captain, is the one who crashed the ship and doomed the crew to death. But it turns out that the character we play as, Jimmy, not only was the one who did it, but also sexually assaulted Anya. The player for the entirety of the game, without realizing it, was not only playing the “villain” of our story, but that what we knew about things was a complete lie.

–

–

–

–

–

–

SPOILER OVER

Interactivity is the greatest strength videogames have when it comes to telling original stories, it’s something that can’t be easily replicated in other mediums unless you’re reading a choose-your-own-adventure.

What I love about both games is that there is no pretense that we’re playing a videogame, and instead, they use that to their advantage to tell an original story and one that pushes the player to keep going. When I think about the games that didn’t work for me, as I said, it’s essentially watching a movie that you need to press “A” for each new dialogue. There must be some level of interactivity beyond just moving from cutscene to cutscene.

1000XResist does a great job of using scifi to explore a very personal topic and go as far as you can with it. (Source: Steam

Both games could have just as well been a movie, or reading a book, but I feel that we as the audience lose something in the process. When a game stops the player to have to take a long walk to contemplate what’s going on, that’s not something we can just fast forward. And again, this isn’t all about interactivity, but pulling the player into the world and having them “move” the story along. This can also be done for exploration games like What Remains of Edith Finch and how the game is about looking through one’s past.

It’s a hard line to walk with designing like this, and no matter how great or high-concept the game is, there will be people who don’t want to play a game only for its storytelling. As another important point, this is not a call to make cheaper stories and try to sell the player on something grander when there’s nothing there, as there have been plenty of copycats of horror and story games over the years. The whole reason why Mouthwashing and 1000XResist work is that the stories are unique and interesting and keep someone engaged from beginning to end. With these games, Mouthwashing has far less churn, as it was designed to be a shorter experience. For 1000XResist, there is quite a lot of churn in the opening chapters, but once the rate stabilizes, most of the audience saw it through to the end.

Where Storytelling Can Go From Here

A lot of what we would define as a videogame has changed in the 2010’s with more developers focusing on storytelling and narrative over gameplay.

A fantastic story is much more of a selling point today than it was 15 years. With everyone’s time being so limited now, it is better to create a short and amazing game rather than one that is trying to hit a certain time limit.

Indika is the most “game” of the ones mentioned today, but it still works with an amazing presentation and original story (Source: Steam)

Indika would be another example of using videogame storytelling and conventions to create something highly original, but it is the most “videogame” of the three talked about in this piece.

Marrying the language of storytelling with videogames when it works can produce something that no one has seen before and elevate the medium. And with the successes of games like Mouthwashing and 1000XResist, I’m hoping we see some more successful and shocking story-driven games for the future.

Be sure to follow me on Bluesky for updates on new posts and the rest of my works online.