I was reading a piece over on Game Developer that gave me pause for a second about whether this is what game design at the AAA level is about now — focusing on analytics and trying to “math” the perfect game. A monumental shift that more people haven’t talked about occurred in the 2010’s with the rise of the indie industry and how it put to rest a lot of the assumptions about AAA development. For today, I want to talk about why you can’t just use numbers to create a great and memorable game, and when the best games have a little “grit” to them.

Objectively Average

Game Design at its core is not something you can really teach or easily put into words. You can explain to someone what good coding is or different art styles, however, it’s a lot harder to explain the differences in feel between Mario vs. Crash Bandicoot, or how Doom 2016 and Doom Eternal are completely different experiences despite continuing a franchise and both being FPS.

In my opinion, feel is the X factor that separates bad games from good games, and good games from award winners. It’s the distinction between titles that people remember for years to come and those that completely disappear within two weeks of launch.

If you don’t understand mechanics and game design, then you end up with a bad game that no one wants to play. However, if you only look at a game from a numerical standpoint and not how it feels to play, you can end up with something surprisingly worse — a game that is remarkably average that no one will remember it or your studio after playing it. For a studio, you’re not going to be growing with new and exciting ideas or having a fan base that comes along for that ride.

Part of sustainable game dev is being able to create games that keep people excited about what’s coming next from your studio. You want them to be interested in your games sight unseen — just the fact that you are working on something or publishing it gets them excited. Studios like Strange Scaffold or New Blood Interactive are examples of this.

And to be able to understand feel at this level means going beyond just playing what everyone loves.

Finding the Rough edges

Part of good game design and good game criticism is being able to look at games beyond just what everyone else is playing. You can’t study game design solely by playing the best games each year. The reason is that you are playing a heavily curated and refined experience with all of its edges sanded down. You’re not going to see the pitfalls of a genre or the pain points, or even know what they are. And sometimes, that off-kilter 6 out of 10 game may have something completely original and amazing in it.

One of my absolute favorite games of recent memory is Astlibra: Revision, a game that is a hodge podge of assets and free music that is as far away from polished or a AAA experience as a game could be. And yet, it all comes together for an amazing time that still feels cohesive. Something like this could have never been conceived by a major studio or someone who only plays AAA games. The same could be said of hits like Balatro, Vampire Survivors, Lethal Company, and many more. These are games that are not the best looking, graphics card shattering, games that required millions to develop.

What these games all share is exploring a very unique and specific aspect of game design and gameplay. Are they all perfectly designed titles that hit their market segments? No. Some of the most memorable games released in the past 14 years all have some element of “chaff” to them — they were not designed by a marketing committee. But what they do have is something that resonates with people, very much in the same way that games like Stardew Valley and Factorio did.

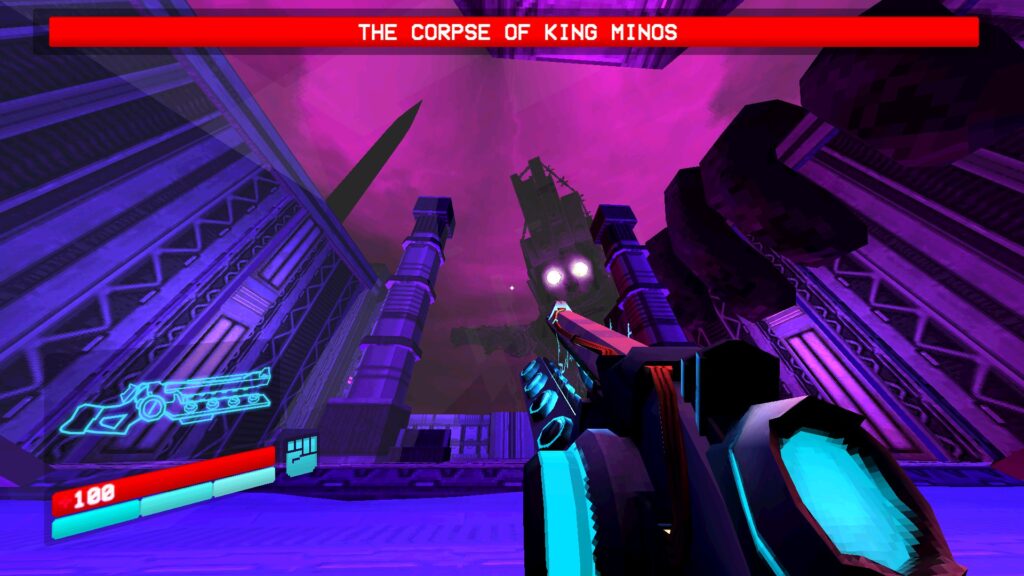

Imagine telling someone 10 years ago that this would be a scene from one of the most successful games ever made (source author).

Designers and publishers continue to chase game success stories thinking that there is some kind of mythical blueprint that if you follow to the letter, your game will be the next million copy seller that will win GOTY from every outlet.

What we find instead, is that those games that try to copy another one end up doing far less than that game. People don’t want to play a game they’ve already played — they need something new and exciting. With Bullet Heaven games, I’ve lost count of the number of them I’ve played that are either “worse Vampire Survivors” or ” Exactly Vampire Survivors but with X theme.” Whereas my favorite examples have all gone in a different direction, such as Brotato, Picayune Dreams, or Death Must Die.

Feeling it Out

Understanding the differences in game feel between bad, good, and masterclass examples of design is something that you can’t quite put into words. You can explain to someone how to code jumping physics in your game; you can’t spell out the exact numbers needed to make jumping feel good. Here’s a bit of an exercise: can you make a platformer with a similar feel to Super Mario World or a shooter like Doom, but you can only watch footage of these games; you are not allowed to play them.

Many designers I’ve seen who try to make games inspired by these classics often do it in the most cookie-cutter way — but there is a monumental difference between how Mario or Doom plays vs. the myriad of games “inspired” by them. I’ve said this point before and it needs to be understood by everyone:

Classic games are not the goal of your game’s design, they are the benchmarks that you need to clear if you expect someone to even think about playing them.

If anyone tells you the perfect way to build a platformer, strategy, FPS, or any game, they are lying. There are always foundational aspects of game mechanics and genres that need to be understood, but these are the “boxes” you need to understand before you can start thinking outside of them. If you think that a consumer will be interested in any game made like it was back in 1989, even the best of that year, you are sorely mistaken. This is also why it’s difficult to explain to someone “this game is great” or “this game is bad” without playing a spectrum of games. Just because you have “jump” or “shoot” as verbs in your game doesn’t mean they are helping sell your game to the consumer.

the best games I’ve played all are about finding that “feel” that works for them, and running with it. (source: Author)

When a game does do something above and beyond with its mechanics, I want to tell everyone about it so that they can then be inspired by it and do something different.

Anyone who understands coding and basic design can make any genre they set their minds to — but making something that will excite people is another matter. You never know when building your game what will resonate with someone. Making a perfectly optimized platformer is one thing, but what about a game about climbing a mountain using a hammer and having to “get over it?” And it’s that ability to create something that resonates that is open to everyone — how so many indie games are able to punch way above their weight and deliver experiences that not even the largest teams with the biggest budgets can achieve.

If you would like to support what I do and let me do more daily streaming, be sure to check out my Patreon. My Discord is now open to everyone for chatting about games and game design.