One of the many balancing acts of game design is the act of creating cool, interesting, unique, abilities for the player to use, and then balancing said abilities within the scope and design of your game. The challenge of all this is creating content that keeps the player interested in playing the game, but at the same time, having to produce equally challenging content that doesn’t step on the toes of your gameplay.

Uneven Footing

What we’re talking about today is on the subject of asymmetrical balance, IE: when two sides don’t have access to the same abilities or content. This post is going to be focusing on player vs. environment, or PvE play, but some of these lessons could apply to PvP.

Over the last decade, as developers have done more in the roguelike and roguelite space, there have been games designed around near inexhaustible ways of playing them. In The Binding of Isaac, it is statistically impossible to have a repeated run with the exception of using the same seed.

For RPG or abstracted design, there are plenty of games built around original game systems, mechanics, and the player is challenged to overcome them. One of my all-time favorites was Library of Ruina, with each boss a giant puzzle of cards and mechanics for the player to figure out.

However, the more you give the player, the more the game needs to be designed to accommodate it, and that presents a problem for developers.

Locking Creativity

A common issue I see in videogames built around customization and player choice is the amount of balancing that needs to be done with it. For tough games in particular, it can feel like the designers are constantly fighting against their own design in an attempt to keep the difficulty in check.

As we’ve spoken about many times, gamers are some of the most analytical fans on the planet. If you give them data and a challenge, they will figure out the best ways to win no matter what the difficulty or complexity of your game.

In Darkest Dungeon 1, several classes had to be rebalanced multiple times throughout the early access period and into 1.0 because players found optimal ways of playing that render a lot of the difficulty of the game moot. There is a thin line you have to walk when it comes to balancing and creating choices in your game in relation to the gameplay systems and challenges you are trying to present.

You need to be able to balance interesting abilities with designing content that can test and challenge the player

This is especially true in RPG-styled games, where the abstraction of the design dictates success or failure.

Everyone knows of the classic JRPG trope of having skills and abilities that are useless because every boss is just immune to them. The more time the player has to spend preparing for a fight means that there is more weight assigned to that fight, and more “punishment” if they lose.

If someone prepares for a boss fight over 10 minutes of picking skills, that’s a far different story compared to having a boss at the end of a 2-hour run that can only be handled in a specific way. Playing through Darkest Dungeon 2, everyone agrees that the third boss is a huge difficulty and time wall for how you are supposed to fight it, and the amount of time lost when you fail.

When you are designing advanced fights in a game where the player has a wide assortment of abilities, you need to be aware of the different options that are actually doable for that fight. Remember, it’s not about saying that every choice is 100% viable all the time, but about allowing different choices to shine in different circumstances.

The Worst Kinds of Choices

In every game imaginable, the choices that the player has access can fit different roles or situations based on the utility and balance present. As the designer when you are balancing your game, you want to avoid creating the following kinds of situations when it comes to the choices that the player can make.

The “Best” Choice

“Best” in this respect can mean a few different things based on the game at hand. If we’re talking about a roguelike or something where the player doesn’t have complete control over how the play will go, best can mean safest. The best choice can also mean the one that outshines everything else to the point where it wouldn’t make any sense not to take it. Imagine two skills:

- Skill 1: Grants 75% more attack, 50% health regen, makes player immune to all magic.

- Skill 2: When the player is poisoned, 15% chance of doing 3% more damage.

Situational choices and powers are some of the hardest to balance properly. The more situational something is, the less they’re going to help someone unless they try to play the game 100% to create that situation. However, in doing so, it is far less difficult to take something that is always good. In Back 4 Blood, the reason why melee builds are so powerful is that with very few cards, the player can do everything from increased damage to health regen at a rate that no other build can come close to. Don’t mistake players who like to create gimmick builds as a form of challenge as the general consumer in a game. Even if that gimmick build is good, the hoops that a player will have to jump through to make it work aren’t going to be worth it most of the time.

Regarding gimmick builds, you also run the risk of creating a scenario in live service games where the best options are paywalled behind getting access to specific abilities or characters that a free player would never be able to afford or reach.

You never want one choice to be considered the de facto best in your game, as it cheapens your design and makes everything else worse around it. When I talk about buffs/nerfs further down, I’ll return to this point.

The Worst Choice

Now we turn to the opposite – when the player base agrees that something is just horrible and should never be taken. This isn’t the same as having something that is situational that could work — this is an option that legitimately makes the game worse to take.

Oftentimes when a developer runs into a situation where people don’t like a choice, they will scramble to try and fix it by any means necessary. At the end of the day, there will always be an option that is considered the weakest to take, it’s just how things go. Again, what you want is for every choice to be viable to some extent.

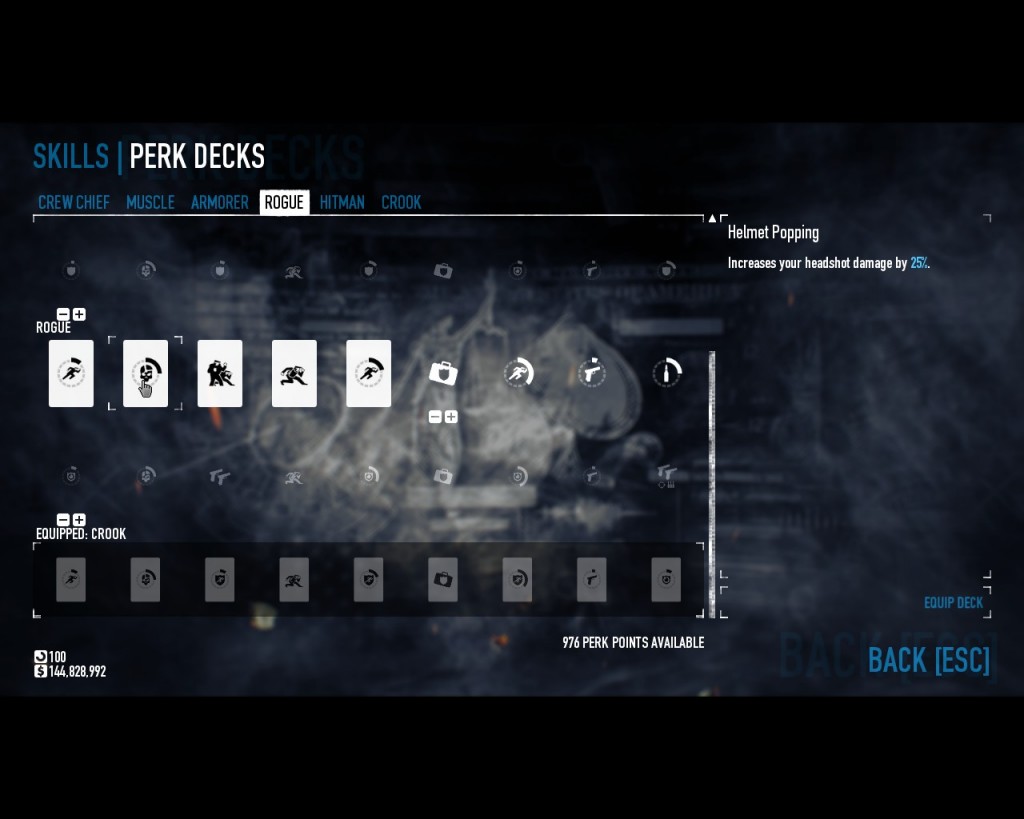

Payday 2’s balancing ran into trouble when perk decks were first introduced that further pushed “the best” choices away from “the worst”

The worst choice also is factored into how someone plays or what someone needs to win.

In Payday 2 for a time, people figured out that dodge builds were the best way to play. What happened was that every choice and skill option became weighted based on how much dodge it provided. If your solution was to just make the worst option have better dodge, it doesn’t fix the inherent balancing issue, and the one I want to talk about next. As a game’s meta continues to grow and change, so will what is considered the best and worst options, and why live service games have a never-ending battle to keep things fresh and interesting.

The Only Choice

A major aspect of how RPG design has changed from the 90’s to today has been a restructuring and balancing of skills. Giving the player access to 80 different skills with only 5 of them viable is not popular anymore. However, what you don’t want to do is create content that only has one way of solving it.

A popular term for this is a “puzzle fight”, where the boss or situation has rules so specific that the player must do only one option to have the best chance at fighting it. This is not the same as designing a boss with specific conditions that limit the player or test the player’s knowledge of the game, provided that there are multiple answers to the same solution. The other exception is if the game is literally pitching this as a puzzle fight, where the entire point of the gameplay is to “solve” the nature of the fight given the tools provided to them.

All of Library of Ruina’s bosses are “puzzle fights”, but the solution is not set in stone to only one fixed build.

If your game has four damage types – fire, earth, water, and physical, and you design a boss that only takes damage from physical damage, then that is railroading the player’s choices.

As I said further up, the weight or the amount of time spent in the game influences the player’s willingness to keep trying. If a boss can only be played after several hours of playing to then only have minutes to figure it out, that’s going to add up to a lot of time wasted getting back to it. However, if the amount of time between creating a build and fighting is only a few minutes, then the player is more willing to keep trying and repeating.

This is why games that are built on player customization are hard to create different challenges around, and why as the designer, you want to avoid creating challenges that remove the player’s ability to do something. Instead, look at ways of giving enemies and situations different tools or unique options catered to that fight that the player must figure out a workaround.

To Nerf or Buff?

When there are issues with an option and the balance of your game, the eternal question will pop up: Do I nerf the option or buff everything else?

What you need to figure out is why people are preferring something over something else:

1: Is this option just better than everything else?

2: Does the option reduce the difficulty and complexity of the game?

3: Is it just more fun or safer to do?

A common misstep I see designers make when they are making a challenging game is to equate complexity with depth. Just because something requires more steps to do doesn’t make it deeper or better:

Weapon 1: If the player hits the enemy with a light attack, it adds light marks to them that can be converted into ultimate marks with heavy attacks, which can then boost your ultimate skill provided you hit the enemy with an opposite element than what you used to apply said marks, but you only have 10 seconds to do it.

Weapon 2: Big hammer goes bonk.

The more unique ways that someone can play a game, without them stepping over each other, helps to act as a form of balance. Instead of worrying if weapon A is better than weapon B, if they both provide different ways of playing, then people will pick them over preference as opposed to power. This is a great case in point in the Monster Hunter series, where every weapon has its own unique playstyle with abilities and options that are only available to it. I’ve said this before, it’s not about designing 15 different builds that everyone likes but making sure that everyone at least likes one of the different ways of playing.

As another point, if people prefer to play a game one way that is different from your intent, and you decide to nerf that way to force them to do something else, make sure to take a hard look at why they are ignoring the other playstyle. In The Last Spell, after launch, the developers nerfed the playstyle of being able to set up automatic towers to act as defensive options besides the heroes. Their rationale was to focus the gameplay on the hero units that you controlled, but nothing was adjusted to the hero skills or that side of the gameplay.

Blindly or haphazardly changing content in your game can end up leaving you with a title that is not working for any group. If you take a hard game and make it too easy, you ruin the audience of people looking for that challenge, and you may not even catch why people found it hard in the first place. And constantly making the game harder by weakening choices and the player’s ability to play will end up frustrating those who feel like they’re being punished for figuring out the game.

What Are Good Choices?

Creating good and interesting choices in your game is about providing the player with different ways of approaching the gameplay, and designing your game around the assumption that the player can and will figure them out. What you don’t want is to be in a constant race to stay ahead of your player base by continuing to up the challenge and remove their ability to compete.

At the end of the day, the best kind of choices is the ones that the player thinks they “stumbled on” when it’s really the unseen hand of the designer guiding them to figure things out. Remember this one point — no matter if you are building a game for experts or novices of a genre, not everyone is going to want to play the game the same way. For every weapon, party member, class, job, etc., there will be someone who is going to try and play the game like that, and they don’t want to be told hours in that their choice was “wrong.”

If you want the player to do something different, then there needs to be a better reason for it than just saying: “Because I want you to.” Look at creating new challenges that require different approaches and figure out how to make something as interesting as some of your other characters or options. And finally, the more you demand the player to “change” or mix up their playstyles, the easier and less time-consuming that needs to be. No one, not even hardcore fans of a game, wants to spend more time having to plan and rebuild their characters than they are playing.

For you, can you name examples of games that had very diverse and interesting choices that all felt viable? Let me know in the comments.

- If you enjoy my work and would like to support me, you can check out my patreon

- And if you enjoyed this story, consider joining the Game-Wisdom Discord channel. It’s open to everyone.