Meta game design has been a major proponent of some of my favorite games; X-Com, XCOM, Star Control 2 and many rogue-likes. Getting it just right is one of the hardest parts and can really sink or swim a title. I’ve been playing Massive Chalice and will have my review up soon, but I want to explore a major problem the game has with Meta game design and how it’s missing the real hook of this kind of system.

Multiple Systems:

First, a brief recap about Meta game design. Meta game design is the development of systems that are meant to interact with each other and are typically seen as two or more game systems working together.

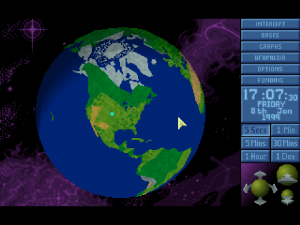

X-Com once again is the perfect example of this type of design; with the game split between tactical combat, base management and simulation and the geoscape system. Each system is connected to one another which turns three separate games, into one complete experience.

We can also see this in a minimal form with titles that offer permanent rewards or upgrades that can appear over successive plays, such as in the Binding of Isaac. In this form, Meta game design simply provides a bridge that links all your plays together so that you’re runs don’t exist in a vacuum. “A bridge” is an important part of this discussion and even works with the system interpretation discussed a few paragraphs up.

The original X-Com’s three systems of tactical combat, base building and the geoscape, all became one experience thanks to the meta-game connection

The point that you need to understand is that good meta game design provides a link; whether that’s a link between plays, game systems or both and when the opposite happens, takes us to the problem I want to discuss.

Broken Bridge:

In order for Meta game design to work, there needs to be a meaningful connection between your systems or plays. When there isn’t, you’re left with a game that becomes very repetitive.

In Massive Chalice, the developers tried to have a similar Meta game as X-Com; in that you take troops that you manage into battle and then upgrade them while managing your resources. The issue is that there is no real connection between the two modes, in the sense that what happens in system A has an impact on system B. You are limited in your options of affecting your troops due to the basic dynasty system and the tactical combat system just doesn’t have enough options between classes to make the different classes interesting.

Compared to XCOM Enemy Unknown, you can see the difference in depth between the meta-game content. Going on missions will make your squaddies grow, which affect their rank and skills that can be used on subsequent missions. Any enemies defeated will provide you with resources to sell or research at the base layer. The variety of improvements will benefit you and give you greater tools for combat.

There are a lot of little details and elements that make up the dynasty system in Massive Chalice, but it’s not at the same level as X-Com’s squaddies

It’s simply a positive feedback loop that feeds into the multiple systems and is what makes Meta-Game progression so compelling.

But any improvements that happen in Massive Chalice’s design are simply surface level and don’t change your tactics or impact future decision making.

Whereas your potential strategy and options will grow or shrink based on the outcome of each mission in Enemy Unknown.

The other part of good and bad meta-game progression is when you’re framing it around repeated plays or using it as a win mechanic.

Keeping the Carrot Going:

I recently played two games built around simple mechanics: Cosmochoria and You Must Build a Boat. The former was a twin stick shooter while the latter was a match three game. In Cosmochoria, I got bored before even finishing the story mode where in You Must Build a Boat, I got all the way through it.

The trick is that both games featured meta-game progression and You Must Build a Boat did it right while Cosmochoria did not. Cosmochoria’s Meta game was one way: You earned crystals or complete quests during a play, which will unlock new content only for subsequent plays.

You Must Build a Boat used a two way system: The boat screen allowed you to set quests and alter the challenge of the run. Once on a run, you could earn resources to spend back at the boat and completing quests will unlock new content and challenges when you get back. Here, the meta-game rewarded players while they were playing by augmenting the experience and it provided goals and rewards to achieve afterwards.

You Must Build a Boat’s boat screen provides two way Meta game progression ; affecting what you do during a run and after

When you’re using a meta-game as a victory or goal, then it becomes the carrot on the stick for the player to go after. Playing You Must Build a Boat, every run no matter what, gave me resources that would eventually pay off back at the ship.

Which in turn, would affect future runs and this would just go around and around and around.

In Cosmochoria however, there’s not enough of a connection to motivate you to keep playing, given the limited Meta game mechanic. If you could unlock new goals which could offer you new enhancements or change how you approach a play, things would be different. Instead, every run started to bleed together, because the Meta game was only working one way. Again, this was also seen in the game Rogue Legacy that despite having an extensive meta-game system was only seen one way.

Simply put, meta-game design can only work as a victory or progression mechanic, when it’s affecting every run of your game. I shouldn’t be thinking, “Oh, in 10 runs I’ll be able to get 5% more attack,” and runs 1-9 don’t matter. Instead, every run should be affected and I should feel like I’m making progress on each run.

Building the Perfect Stick:

Meta game design when it works has been instrumental in elevating video games either small or complex, but when it doesn’t, it can sink a game’s design quickly. While it may seem easy to add persistence to your game, there’s more to meta-game design than just a second system or three.

Everything has to connect and that connection must work to all game systems or the point is lost. If the pull is there, it will keep someone coming back after their 10th, 20th, 30th and so on run. I’ve spent over 100 hours playing the Binding of Isaac and Rebirth; I don’t think I’m going to get that far in Cosmochoria or Massive Chalice due to their attempts at a meta-game.