Videogame difficulty has often been a polarizing topic — whether we’re talking about the “live, die, repeat” cycle of roguelikes, the higher than normal skill floor of soulslikes, or even having a casual/”story” difficulty level. Regardless of where your stance lies on the difficulty in games, there is one thing that is clear, the philosophy surrounding it has changed, and it’s an important point about game design today.

Metrics-Driven Design

The game industry originally started with the arcades which defined game design for several decades. Part of this was in the form of “metrics-driven design”: that games had to be built to get maximum dollar value out of each consumer. In arcades, this meant increasing the difficulty and introducing systems that would make it easier for the player to die, and of course, spend more money.

On consoles, developers typically designed games to be confusing to play, extra difficult, and in some cases require a strategy guide, so that it would take a long time for someone to beat it. Many classic examples of difficulty were hard due to these extra elements instead of just for the gameplay itself. Ninja Gaiden’s infamous final chapter was frustrating because the player’s progress was lost each time they died during the final set of bosses.

There is a common point to these systems that I hope the reader picked up on — each system punishes new and lesser skilled players specifically. If you have ever watched speedruns or master level play of these games, those players are not bothered at all by them. When you are good enough at a game, any kind of punishment system is not going to impact you no matter what, but they are still going to affect new players. The worse point is that these systems don’t add anything to a game and only hurt people who are still learning it. Even though many gamers will treat difficulty like this as a badge of honor, implicitly targeting new players with difficult systems is not how you want to design a game today.

Targeted Difficulty

Consumers have different thoughts on their experience when it comes to playing games. Some people want to be tested, while others just want to see the story. To accommodate a larger market, we have seen developers today embrace a more controlled form of difficulty. When we talk about difficulty in this context, it’s not just about making the game easier, but also ways of making it harder without adding frustration.

The first way is the most direct: difficulty settings. Many games are designed around multiple difficulties varying between having no challenge and playing the game at its hardest. In my opinion, this is still a band aid fix, because the developer is still doing blanket sweeps of difficulty adjusting. As we have discussed before, it is very easy to create a game at either extreme of difficulty by just changing stats around. However, that is not looking at the game itself to figure out what are the major pain points.

There are games that allow the player to finetune specific parts of the design in terms of difficulty. If you’re not the best at stealth, but good at combat, you could make the stealth sections easier and increase the difficulty of the fighting. Titles like The Last of Us 2 and Way of the Passive Fist allow someone to adjust each system like this to allow someone to play the game at their preferred level. Player controlled difficulty is an essential part of improving the approachability of videogames. More importantly, it helps developers improve by being able to spot and understand what parts of their design may become frustrating to players and adjust them going forward.

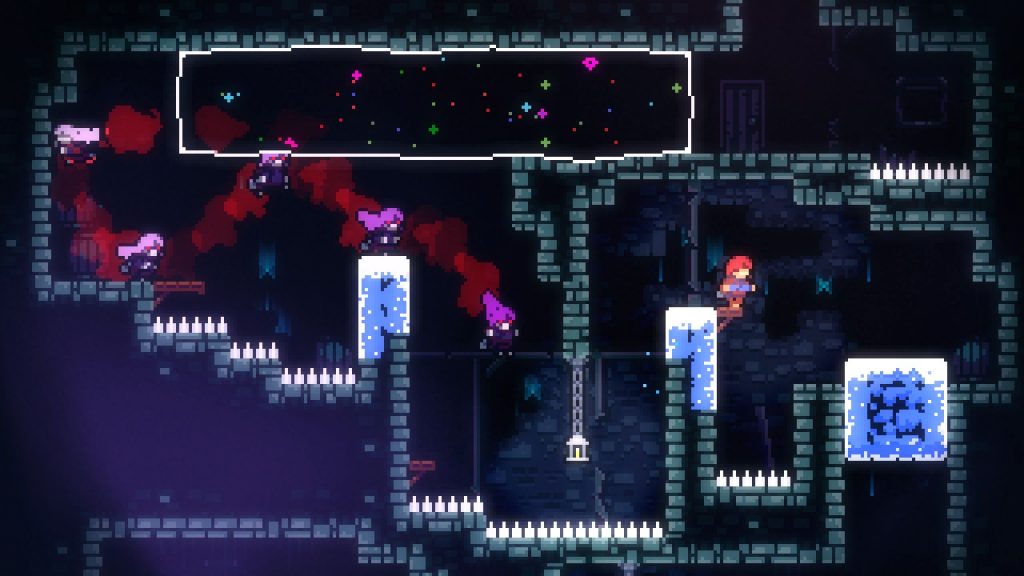

Hades, which will come up in the next section as well, has “god mode” specifically for newer or lesser-skilled players who want to enjoy the game and see the story, without the need of twitch-based skills. By turning it on, every time the player dies they will receive a permanent buff — guaranteeing that eventually someone can just win on bonuses alone.

Monster Hunter World was a good example of having implicit ways of making the game easier and more accommodating for new players. As we spoke about, Monster Hunter is a series that defined itself on opaque and challenging gameplay for more than a decade. With the latest iteration, the developers completely redid the onboarding, provided easier ways to set up groups, while still having the depth and challenge fans have come to expect from the series. Someone can try and solo almost every fight in the game, or always have a group to play with.

The “nuclear” option when it comes to player-controlled difficulty is giving the player access to a “cheats” menu that they can use at their whim. Celeste famously allowed someone to turn on invincibility, infinite jumping, and other modifiers if they got stuck at any of the challenging sections. If you want to guarantee game completion, this is a surefire way.

With all that said, we have been talking about making games easier, but this discussion is also about increasing difficulty to create challenges, not frustration.

Rewarding Challenge

Let’s start with a simple, but needs to be said point: LEARNING A GAME SHOULD NOT BE DIFFICULT. There are still designers out there designing bad tutorials, or purposely leaving the game hard to figure out, as a way of driving challenge. That is a game design sin in my book and not where you want to focus on challenge. As always, tutorial and onboarding are major topics that would be too big to get into in this post.

A good challenge in a game is about raising the stakes and rewards for the people who want it. There is a wide margin of fans of a genre who just want to play it, versus fans who want the absolute hardest version of a game. Whenever we have discussions about making games more appealing, many people quickly jump to the idea of “dumbing down” a game and view approachability as a negative. What we have seen from games today is following a philosophy Nintendo has done over the years when it comes to difficulty — provide a baseline experience for everyone, rachet up the difficulty for those that want it.

The concept of progressive difficulty that we are seeing from modern roguelikes is an example of this. The design of allowing the player to pick and adjust a game to make it harder in interesting ways. Ultimately, the developer is providing both the baseline for playing the game and the tools for the player to make it harder if they so desire. Regardless of the actual skill level, someone who wants to play the game will get an experience tailored to their playstyle without affecting anyone else. There can be unique rewards and bonuses for playing the game at a higher challenge, but it should be possible to see the story through to its conclusion on the baseline setting.

Difficulty for the sake of difficulty is not the selling point it was a few years ago. For developers who are still chasing those hardcore fans, they are going to find a dedicated, but very small, group of consumers.

Fair and Tough

In previous discussions about difficulty we have talked extensively about the soulslike genre, because Demon’s Souls is the game that showed people that difficulty could still be applied to major hits. The question always then turns to: “How do I make a hard game that’s fun?” I have played many games from indie developers who are all trying to capture the magic of Dark Souls or Hollow Knight… or any popular and challenging game. For most of those games, they all end up selling a fraction of those popular titles, even though they build up ravenous fanbases.

Hollow Knight is another game cited for its difficulty, in spite of having really solid gameplay to go with it

La Mulana 2 is a good-bad game. Just by saying that, I already know this post is going to get flamed by its fans. The series is one of the deepest and most challenging metroidvania titles around.

It is also one of the most horrible games when it comes to onboarding, approachability, and even just playing the thing. This is a series that prides itself on getting the player completely lost, introducing puzzles with no in-game explanation of what the solution could be, and having a guide on hand is required by most people. Nothing about this series could be considered accessible, and any attempts to try and make it more mainstream are meant with backlash by its fanbase. La Mulana is not the exception, there are plenty of these games that never hit the mainstream despite having original and great gameplay to them.

The problem is that no matter how great the gameplay is, it is always surrounded by frustration. Most people know the phrase “tough, but fair,” but when it comes to game design it should be, “fair, but tough.” Too many developers lean into difficulty as a crutch when it comes to gameplay. You can see this in frustrating titles where developers throw up their hands and say, “it’s supposed to be like this,” as if that magically fixes frustration.

A frustrating game is not a good game, and all these titles that leave-in, or are designed, to be frustrating are shooting themselves in the foot. Frustration is easy to make, but a balanced game is a challenge.

The New Difficulty

To wrap up this post, let’s recap what difficulty means today. People expect a fair and balanced design regardless of the intended audience. That means providing an experience that caters to as wide of a market as you can — from someone who is a beginner to the genre all the way to the experts. That last sentence is an important point about approachability that we will return to in another post. Remember, this discussion is not about gameplay, but skill levels. In an earlier post about approachability I said that there is a vast difference between someone not liking a specific genre, and someone not liking your version of a genre.

Taking a closer look at approachability and making your game appealing to a wide range of fans of that genre gives your game a greater chance in the market. As another benefit, it also helps to improve your skills as a developer in terms of understanding and then troubleshooting pain points. Many of the most popular and best selling games being released today have done more towards approachability and accessibility.

If you’re going to make something hard, then you have to make it interesting. This is where the idea of progressive difficulty in roguelikes, new game+ modes, or providing unique rewards for making the game harder come in. Just blindly changing stats to make a game easier or harder is not good enough in today’s market. Hades is once again the best recent example of this philosophy — with systems in place to allow anyone regardless of their skill level to be tested and still enjoy the game.

Blindly focusing on one extreme spectrum of gamers will often lead to a game that is laser-focused in its appeal, but not much else. I know someone will argue that point being positive, but there are so many games that could be improved with greater care to approachability. And I have to remind everyone that even Kaizo games — some of the hardest and most mechanically-driven platformers around, have been improved to be more approachable in design and structure without losing that bite.

The all-important mantra when it comes to defining challenge is that the player should always feel like it is their fault why they have lost, not due to the game’s design. Again, playtesting is key, and understanding the line between fair and frustration can lead to great games that can be as easy or as hard as someone wants it to be.

If you enjoyed my post, consider joining the Game-Wisdom discord channel open to everyone.