Elden Ring continues to dominate the discussion when it comes to game design, approachability, and marketability for games currently. As I was dreading, I’m seeing people use it as a means to attack UI/UX and approachability, and those attacking it saying that because it’s not fun for them, then it must be a bad game. When it comes to studying game design and talking about mechanics, “fun” can be viewed as a four-letter word and it’s important to understand why.

Ring Around Player Centric Design

Whenever we talk about concepts of “fun” in games, it reminds me of the talks surrounding “player-centric design.” This is the idea that a game should be designed for anyone to be able to beat it. I remember first reading about this in the early 2000s and I disagreed with this principle then and I still disagree with it now.

Some critics will argue that this is going against UI/UX design, but I feel that it goes against good game design. Good game design and marketing is about pinpointing and designing your game for an intended audience, and then using UI/UX conventions to improve approachability and accessibility. Some of the most popular and innovative games to come from the indie space are not about appealing to everyone but presenting an attractive and unique package that makes you want to try and play it. The UI/UX discussions are then focused on making the game more palatable to a wider audience without losing sight of the intended experience. Most people are not going to finish the games they play for one reason or another, as evident by the many low clear rates and high churn rates I see when I examine titles.

The debate surrounding Elden Ring is certainly evidence of this — with the game earning massive praise and sales while bucking the traditional trends of AAA games over the last decade. So much so, that there was a minor meltdown on game dev twitter from developers who couldn’t understand why the game is doing so well.

The Marketability Mistake

Part of the problem with the discussion of fun and the market is that there are elements of entitlement here for both consumers and developers. For consumers, it’s that by buying a game, you are entitled to having the experience be 100% catered to you and your tastes, and if it’s not, then the game is bad because of that. For developers, it’s possible to design a 100% universally loved game and it would be impossible for someone to hate it. I feel that there has always been that chase for developers and consumers to find “the perfect game” — that one title that everyone must play, or the game that goes on to define what a videogame is.

There are developers, who I feel believe that certain aspects or designs of a game are inherently “good” or “bad” and are the reasons why a game succeeds or fails respectively. Last year, there was a discourse surrounding the idea of people really taking the labeling of certain games as “wholesome” to an extreme level. That these games were somehow inherently better or healthier to play compared to other games.

Challenging games are often the hardest to review accurately, especially with a very specific intended audience

To bring this back to the argument over “fun”, the mistake is assuming that if you’re having fun then the game is good, and if you’re not having fun, then the game must be bad. This is part of the challenge of studying game design and mechanics and the fact that it’s not about your overall enjoyment of a game, but whether or not the developers achieved the goals they intended with the design and systems. As a consumer, you are well within your right not to like a game for whatever reason, but it’s a different matter if you’re declaring a game as being “bad” or “wrong” simply on that metric. There are a lot of games that I personally didn’t like but could still explain why someone would like these systems.

To do that, you need to step outside of your own opinions and thoughts to understand what the mechanics are trying to accomplish. There’s a huge difference between saying “I don’t like this, so it must be bad”, and “I don’t like this, but if you enjoy it, then you’re going to like this game.” Conversely, it also means that just because you like something, doesn’t mean that it’s automatically “right” or that someone is wrong because they don’t like the same game.

Examples would be games like Getting Over it With Bennett Foddy or Jump King. These games are built on frustrating controls. However, this is not a case of a developer not understanding how to design a game, but explicitly building the game to be this way. In that respect, even if you don’t like it or don’t find it enjoyable, it’s an example of a developer aiming for a specific goal/experience and nailing it 100%. There are areas where I can, and have, criticized Elden Ring and deservedly so, but they are about the mechanics and balance of the game and not about me personally having fun or not. Those complaints are again focused on the core gameplay loop and the goals of the developer as opposed to personal issues.

And this gets at the heart of the matter when it comes to using the word “fun” to define the quality of a game. Just like there is no one size that fits all game, there is no one universally fun game that everyone can enjoy.

The Cruelty Market

There are perfect videogames for people to play, but they’re still not meant for everyone. I have my own perfect game, just as everyone reading this has theirs. What works for one person will not work for everyone else, and this is on full display in the indie space. I have played hundreds of indie games at this point that are unique, spikey, and were never intended to blow up in the mainstream. Sometimes, you have games like Disco Elysium, Stardew Valley, or Celeste that do become massive hits. However, I can guarantee that the developers didn’t start their development with the goal of making a massively mainstream appealing game, they just wanted to make that specific game.

Indie developers have been pushing design and systems in unique directions for over a decade now. Part of the reason for so much praise of the indie space has been a willingness to go places that AAA, or mainstream, developers couldn’t risk their studios on.

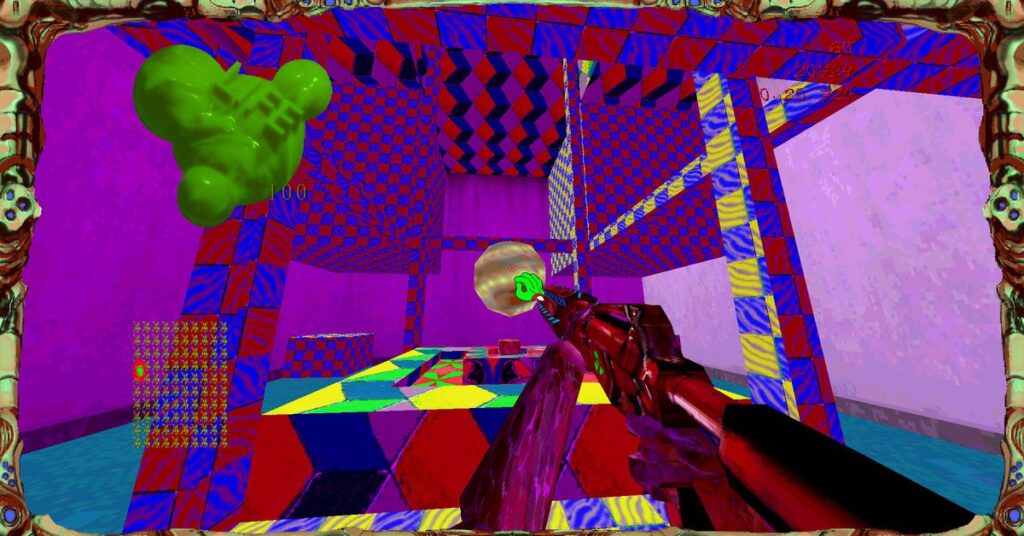

A case in point is the recent trend of remaking early 3D and emulating Ps1/Ps2 graphics as an aesthetic. Whether this is done for a modern retro horror game like the Dread X series, the recent platformer Sephonie, or the almost “anti-fun” design of a game like Cruelty Squad, as the game was intentionally built on as many weird and esoteric systems that one could fit within the strange world of the game.

“successful” game design is not about you having fun with it, but the intentions of the developer

And this takes us back to Elden Ring and how it’s not so much an example of From Software “getting it”, but the rest of the world catching up to the studio’s design philosophy.

I may not like Elden Ring as much as other soulslikes by From Software, but those issues are more about the nuts and bolts of the game compared to the overall package. And again, even with my problems with the design, that is not me saying that the game is “bad” or “wrong” because of them or because I didn’t love the game.

For the many people who have been going out of their way to attack Elden Ring as a “wrong” game, it makes me think about how little they have played games outside of the mainstream, if your only exposure to indie games is something like Celeste, Hades, or Disco Elysium, that’s not really examining the indie space. There are games that make Elden Ring look simple by comparison.

Normally I don’t link to Twitter when I do design posts, but this thread by the designer of Adios really lands so many of the details I’ve been talking about when it comes to studying game design. And for one final lightning round of points to make:

- Just because a game is challenging doesn’t mean it has bad UI/UX

- Just because a game is challenging doesn’t mean it has good UI/UX

- Just because you hate a game doesn’t mean it has bad UI/UX

- Just because you love a game doesn’t mean it has good UI/UX

The Art and Science of Games

This whole discussion really drives home a point that I made on a recent podcast. There is both art and science when it comes to game design. No matter how creative or artistic your game may be, all successful games have a good foundation when it comes to their designs and systems. Without that, it’s like building a house or constructing a car without any solid framework or planning. Sometimes, this can lead to games that are the exceptions to the rule and become huge successes, but that’s not the gamble most professional developers should take with their studios.

And that foundation comes from understanding game design, not game dev which is its own area. The craft that goes into game design is a completely different skill set compared to the rest of game dev. There is a reason why there is a vast difference between good and bad platformers, despite the genre being so old and recognized — the successful games understand what elements define a great platformer, and the ones that don’t succeed often ignore or don’t get those points. And those elements are not “opinion” or “up for debate.” Not every game is intended to be a rollercoaster of fun every second or appeal to everyone. That also doesn’t mean that every game needs to follow the same direction and design that everyone else is doing.

“Fun” and “wholesome” are okay descriptors, but not the metrics to judge a game on

I can think of plenty of games like Frostpunk, This War of Mine, That Dragon Cancer, which deal with topics and themes that aren’t “fun” in the same way that critics like to use the word, or “wholesome” from last year. The games that have blown up among indie circles achieved that by being different, understanding the design and mechanics they wanted to build, and doing something that hasn’t been considered before.

For you: Can you think of a game that succeeded by not following the beaten path of a genre or game design philosophy that I didn’t mention here? Let me know on Twitter.

If you enjoyed this story, consider joining the Game-Wisdom Discord channel. It’s open to everyone.