With all the live service games I’ve played over the years and the research into my book on free-to-play design, I haven’t stopped to try and catalog the different content that can be made for mobile and live service, as it’s a fascinating breakdown of what goes into making money in these games and why there never is enough.

For this post, we’re going to organize things into content that is directly purchasable: IE: DLC, banners, gachas, etc., and content that adds to the game that is meant to keep people invested in playing that doesn’t directly have a cost to it, and yes, that phrasing is correct.

The Purchasables

Let’s get the easy content out of the way first — all the stuff you are going to be charging players for. As I’ve said in previous design posts, if you’re making any kind of multiplayer or live service-focused game, you must be thinking about how it’s going to be earning money to fund continued development.

Purchasable content comes in two flavors — permanent and consumable/temporary. Permanents are all the high valued elements that become permanently available for someone’s account — new characters, new cosmetics, weapons, gear, and the list goes on. Consumables depend on the game, but they are meant to provide some kind of short-term boost if/when the player needs them. One of the most common in the live service space is having a means of recharging energy or earning in-game currency when applicable.

Part of the economy of balancing your content in this respect is the cost that goes with it. This is a topic that really needs a formal look at and agreed upon standard — you have some games where the pity (guarantee chance of getting something) still equals hundreds of dollars, and some games that “offer” the player the option to buy a new character for $400+. Likewise, some games have consumables that are very easy to get and bank, while others take forever to earn; something that will come up again when we talk about content further down.

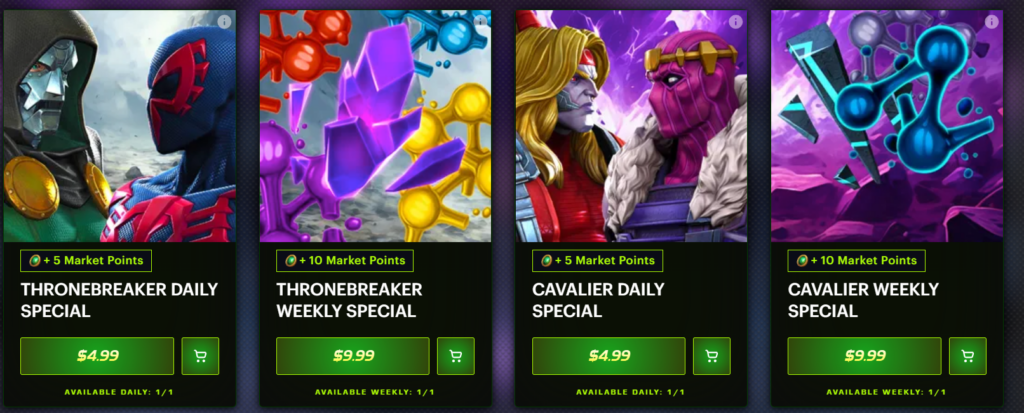

Contest of Champions features both an in-game and online store, with different purchases for both. (Source: MCOC)

This category also includes any special sales or limited-time offers you wish to put out for players. Many live service games these days will have limited-time deals around major holidays or the anniversary of the game’s launch. Developing the economy of your game is a bit above my pay grade without having first-hand experience doing it, but this is something you need to think about when it comes to the lifespan of your game.

Purchasable content is going to fund your game, but at the same time, you’ll need to settle on what that means for your game and your player base. Expecting everyone to spend at minimum 10 grand a month is not going to happen — and you must still provide a means of progressing for people who don’t want to spend.

That last point is always a contentious one for fans and developers. There must always be a way for someone without spending money to make progress in a reasonable timeframe– you can’t say that your game is free-to-play friendly when it could take a year to earn enough resources that someone could get for $5.

The dream condition is for your game to be so good that spending money is completely optional, and yet people still do it because the content is that good and they want to support the developers, with the major example being Grinding Gear Games with Path of Exile.

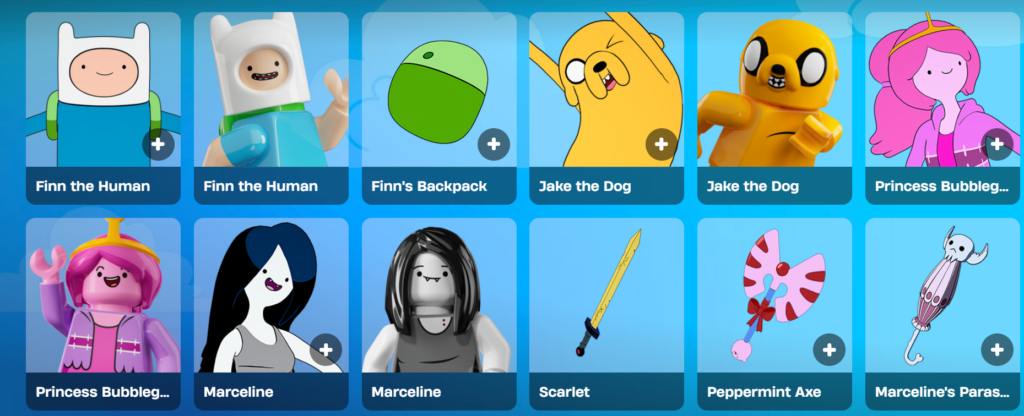

Cosmetics as we’ve talked about go all over the place — something as simple as a new color palette all the way to brand new costumes that fully change how a character looks and sounds. For a lot of hero-focused games, cosmetics tend to be one of the biggest and easiest money makers, the most recent example being Marvel Rivals with its skins — some of which are locked behind ranked rewards, to the point that services even exist like Marvel Rivals rank boosting just to help players secure those high-demand end-of-season cosmetics. If you’re building a game around custom characters as opposed to known IPs, Path of Exile with its different skill and costume personalization is another great example to follow. The point about personalization is allowing players to make their character(s) uniquely theirs to look at.

You may be wondering where are the maps, game modes, story content, etc. here. The answer is that for live service games, you cannot sell people content that is meant to grow the game. Not only does that conflict with the free to play/live service nature of the design, but it also means that it would split your consumer base in terms of what people can access/play.

Skins are a tried and tested way of getting money from fans looking to spruce up their characters and stand out. (Source: Reddit)

One unusual piece of purchasable content I want to mention is the use of season passes. A season pass is a collection of content that unlocks more depending on how long someone plays or completes objectives. For many content-focused live service titles, a season pass can be good value depending on what’s being offered. With Limbus Company, their pass is often enough to provide enough free resources and currency to get access to all the characters for that season (for the most part). There are fans of games who only buy the season pass and treat it as a seasonal or yearly subscription for good stuff.

Purchasable content will be the most regularly updated piece of content in your game, as without it, you’re not making any money. With non-purchasable content, it’s time to talk about what people are going to be doing in your game and the different phases of it.

Daily Content

Daily content is the reason for logging into a game day after day. While I’m not personally a fan of this, you still need to think about how long someone should be playing your game for on a day-to-day basis. This is not the same as doing the other forms of content which are typically one-offs and that your hardcore fans will try to blaze through as fast as possible.

Daily content is meant to provide useful resources that the player is always going to be needing in some form. Popular options include currency, energy refills, gacha currency, and consumable resources. For games that allow the player to upgrade characters and/or gear, daily content will also include the means of upgrading. As someone goes through your game, it is important to regularly upgrade this content to reflect what the player is needing at a given time — if someone is level 60, earning level 20 resources is not going to work. Daily content can also go through updates over the course of a game’s lifecycle — if the overall progression in your game changes and grows, so must the daily content.

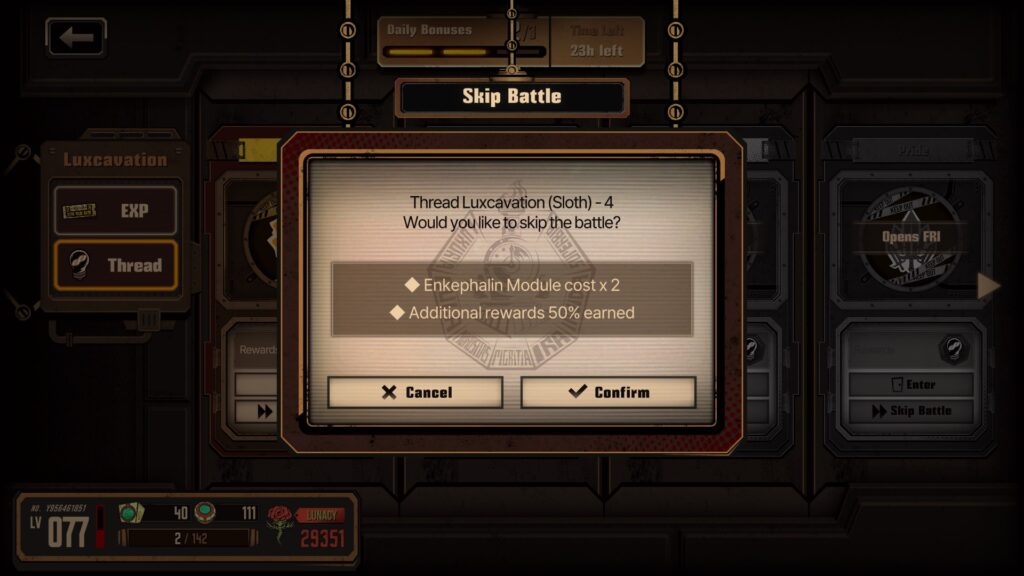

Another point is that as someone spends more and more time in your game, they will want to do less repeatable content. You must provide a means of getting these resources as quickly as possible because long-time players will become annoyed at having to do the same 20 minutes of play every day until the day the sun dies or your game (whichever comes first). At some point, it should be possible to just auto-skip or auto play daily content for an account that has reached the very end of the progression.

Some games split daily content into specific days when they are available, and that is another practice I’m not a fan of. With people already having limited time to play, telling them they need to play on specific days doesn’t sound right.

On the subject of limiting resources, another factor that some games have is that the player can only do a resource event X amount of times per day before it is locked out. This is designed to A: require the player to play daily and B: create a hard limit on how long it takes for someone to earn resources. If we’re talking about progression-related items, a limit can be important to keep players from advancing to quickly. However, consumable items, or those that someone can chew through rapidly, I don’t feel like there should be a limit on those. And the reason why has to do with content that is meant to be very challenging that I’ll talk about further down.

At some point, you want daily play to be as quick as possible, and even skippable, for people who have done it all countless times, (Source: Game)

Daily content is something that can also depend on the types of modes in your game. For those that have PvP or alliance/guild content, which may extend the amount of daily play. Just remember, the more you expect someone to commit daily to your game, the harder it’s going to be to convince casual/core players to keep playing. There’s a difference between wanting to play a game for hours on end and being forced to play a game for hours on end to keep up with everyone else.

Major Content

Now we get to the first meaty point — content that moves the game forward. For competitive games, these can be new maps, new characters, etc. Multiplayer games today tend to take a season approach — releasing major content as a new season or chapter in the game and building their marketing around it. For story-focused games, this includes new chapters, new boss fights, cutscenes, music, etc. This is the kind of stuff that live service is meant to fund — turning a game with six months of content into one with years.

When planning the timeline of your game, you must be thinking about the frequency and schedule for content of this size. This is not something that you can release, realize it’s not working right, and then turn it off for a later date without causing a riot among your fans. On top of that, the release of this content must be communicated to people playing your game. The best live service games turn major content releases into special events for the community, such as the release of a new episode in Arknights.

Another challenge is that major content needs to evolve your game: there must be something new and exciting that hasn’t been seen before. Games like Arknights and Limbus Company try out new rules and mechanics for their later chapters, on top of new storylines. What is often the killer of live service games is that they have an amazing couple of months, and then no new content gets put out, the players become bored and start leaving. Or the content that gets put out is just variations of what’s already there — instead of fighting blue enemies, you’re fighting red enemies. For multiplayer, seasons are also the time to make balance adjustments, often to align with any new characters or mechanics introduced in the coming season.

What often separates the live service games that can survive and those that end up burning out are the ones that have enough “levers” they can pull with adding in new content. One of the reasons for the longevity of Marvel’s Contest of Champions is that the skill-based gameplay lends itself well for developing new and harder variants of enemies, new boss designs, new characters, etc. This is also where I have an issue with Arknights: the good characters are so good that they tend to overshadow everything else, including hard content.

Arknight’s major story releases will come with a new banner, new challenges, and rewards for everyone (source: Hyperglyph)

Many live service games have died due to not realizing the importance of new major content on a frequent basis. There was this tendency to release the game, put out one update, and then do nothing and hope that the money continues to roll in. For live service specifically, you have a window of about 1-3 months after release to start getting new major content out before people get bored. And again, this does not include gacha/characters, which should be added frequently. As I’ll talk about further down, you can use content already developed to keep people playing, but that is more of a stopgap than a long-term solution.

For multiplayer games or those where a single character or map is a huge deal, you can get away with longer turnaround times. Dead by Daylight turns their major releases into “Chapters”, with each one being a major event, having a season pass, and being a huge point for the game and they come every few months.

Player Generated

The next kind of content is those that rely on the players and this can mean a lot of things depending on the game. Many mobile games allow players to share characters or request help in the form of a character from someone else’s account. In games with a predominately singleplayer focus, some games have multiplayer available at certain times for PvP or guild battles.

This is something that greatly depends on the design of the game and the skill and creativity of the designers. Even a single player game like Arknights had some coop modes available for a limited time with two players taking on a map together. On the other hand, you have many browser-based games and guild-focused ones that are all about playing against other players/teams/guilds.

With multiplayer-focused games, player-generated content is the entire reason for playing — if there’s no one around to play with, then it’s not possible to play those games. This is why many of the live service multiplayer games released over the 2010’s crashed and burned: no one was there to play them, it wasn’t possible to get matches going, and then the entire thing went end of service.

In this respect, you need to make the ability to play with other people as painlessly as possible. This includes having different modes of play — general matches, ranked, seasonal, etc., and providing the tools and options to avoid people meant to ruin everyone’s time.

For multiplayer games, you can get away with fewer content releases, but the ones that do come, must be game changing. (source:Superherohype)

For games that do both — provide single player or PvE content, and have a PvP option, you need to be aware of how the content is being approached. There are people who will never want to do PvP, just as there are those who only want PvP. It’s a delicate balance to strike when it comes to rewards and engagement. With Contest of Champions, the meat of the game for many is the story/chapter maps that are introduced along with the endgame content. For others, it’s all about the arenas, battlegrounds, and alliance play. You need to be careful not to cross the streams, in a manner of speaking- telling someone who only wants to do one mode that it is required to play both.

This next point is too big for this post to get into, but when you are balancing content, you need to be mindful of how something plays when it’s the player using it against the AI and a player using it against other players. For single-player focused games, this is not a concern, but when you’re dealing with PvP modes, it can prove to be tricky to balance your abilities. What MCoC does in this respect is that characters can have different behaviors or rules for their abilities and attacks depending on whether they are an attacker (for the PvE content) or a defender (used in PvP). Remember, adjusting characters that people have spent money on is a very risky prospect and can risk angering your fans. Likewise, leaving broken characters that provide a huge advantage to those who got them can also annoy people.

Whale/Endgame

Now we come to the unusual content for games like this — retaining your hardcore fans. The endgame or late-game content is designed for the whales/people who have played your game the longest. Creating content of this kind is about two things:

- Delivering challenging content meant for people who have almost/every bit of progression done.

- Giving them rewards to keep them engaged and to chase after

Marvel: Contest of Champions has multiple end game modes designed around the hardest challenges in the game and provide account-changing rewards for people who can get them done. Not only that, but there are characters who are only “easily” obtainable by completing specific challenges. An example would be “Deathless Thanos”, who can only be unlocked by accounts that have all the other major deathless characters and completing a very specific, and very difficult, piece of content.

The problem with content like this is deciding whether or not the general consumer should be able to do them at some point. This returns to the overall planning of your game — do you expect everyone to be able to do all the content in your game? With MCoC, the amount of good characters and resources that are practically required puts their endgame content above most people’s ability to play/pay to do them. Arknights takes a slow and steady approach by having challenging maps meant to give gacha currency each week and special modes that have been added over time. However, nothing gameplay-wise is content locked behind the harder modes.

end game content in MCoC comes with unique and exclusive rewards that both act as prestige and major upgrades for accounts that can do them (source: Reddit)

In a previous post, I mentioned roguelike modes become increasingly popular to have as end game content. With Limbus Company, they do a mix– a weekly roguelike mode to earn gacha resources and endgame content in the form of the “refraction railway” that tests players with challenging fights meant for people who have access to the best characters. The difference between the three games is that MCoC purposely has characters and resources only obtainable in their highest difficulty challenges, while Arknights and Limbus Company treat them as just bonus rewards to the base experience.

The point about this kind of content is that it’s meant to entice your hardcore players and whales to go after and provide a long-reaching carrot on a stick for core players to maybe go after. However, there needs to be a path toward it that doesn’t require giving the game access to your bank account. Some hardcore fans will argue that the point of this content is meant to be a reward/challenge for the whales, but the more content you design that the majority of the player base can’t access, the more they will feel like they’re being left out. In an earlier post I mentioned being economical in terms of designing content. You don’t want to spend six months of development working on content that only 3% of your players will ever do. Returning to the previous section, waiting a year for a new story mode to drop, and the only thing that’s coming month after month is the hardcore content, a lot of people will get tired of waiting. In effect, you need to be working on both kinds of content simultaneously for the best results.

Another problem that you will have is the rewards for this. The rewards offered have to be good enough that people will want to do it, but at the same time, they can’t be required for overall progression, especially for core players. With MCoC, I’ve managed to reach Paragon which is one milestone away from the last one currently in the game, Valient. Unfortunately, the requirement for it is to get champions to a certain rank that 99% of the content in the game doesn’t give you the resources for it. The only way to get them are to either spend a lot of money or go for the hardcore content which once again requires a lot of consumable resources to even attempt.

For some of you, you might be thinking with all these problems and challenges that you don’t need hardcore content in your game, but you do. There needs to be a way to separate the hardcore needs of your players from the core and casual audiences. And for multiplayer-focused games, you are not exempt from it — there should be ranking modes, professional modes, something that keeps the ultra-competitive fans of your game away from everyone else. The worst thing for multiplayer live service is to have your elite players mingling with your casual and core audiences. This is why multiplayer games will always have “general” and “ranked” ways of playing.

And for an obvious point, if you extend the endgame with new content, new reward tiers, and new progression, then the rewards and future content must be relative. If the only way to progress is to have six-star characters and options, and the rewards being offered are for five stars, hardcore fans are going to get frustrated.

End-game content like this is typically not meant to be repeated forever. There will come a point where the player has unlocked everything in a mode or that mode is no longer providing enough incentive. Therefore, just like with your story content, you must be thinking about adding in new endgame content as time goes on.

Recyclable Content

Designing content for a live service game is no easy feat, and developers who have managed to survive in this space know that you can’t be putting out highly polished and original content every month with no breaks. This was the fallout of the early MMOG revival when developers tried to embrace live service and rapid development.

What you need is to think about content that can be recycled. The “recycling” in this respect is that it can be used after its initial release in one of two ways.

The first is repeating an event that allows players who missed it the first time to experience it and provide players who already did it with even more rewards and resources for doing it. Both Arknights and Limbus Company, among other gacha games, have rerun events for this very purpose. It allows them to fill in dead time that they are busy working on new content for the game. Dead by Daylight takes a different approach. All their chapter-based challenges and rewards remain available forever after their debut. Instead, the limited-time rewards are the seasonal pass content that goes away after the season is over.

Another way is to have seasonal or limited-time content that is meant to be a special event and bring it back without formally integrating into the base experience. What you don’t want is to have content that only serves the purpose of keeping people entertained for exactly one week after launch, or something that is never going to be repeated again.

Limited-time content runs the risk of making it harder to get into a game after the fact — as permanently missing something cool is not how someone wants to start a game. (Source: Fortnite)

This is the issue that I’ve seen with the chapter approach to Fortnite, and how each new chapter is about taking all the rules and rewards of the previous one and throwing them out. Not only does this waste content, but it can leave a bad taste in the consumer’s mouth- that joining a game after X amount of months or years means never being able to access everything in the game and missing out on permanent rewards. With MCoC while the endgame content has evolved and grown over its decade, all the different modes with their respective rewards remain open all year round.

Moving Through the Game

A big point about the lifecycle of a live service game and how sustainable it is comes down to one question — how does someone move through the content in your game? As the developer, you are going to have to decide on what content someone must do, and what content is meant for niche players. The “story” content in your game, or general play content, must be playable by everyone regardless of their spending level. This is a growing issue with Limbus Company, as the story content continues to progress and keep with the increasingly growing level cap and complexity. For people who aren’t able to keep getting the best characters, it becomes harder to make progress in the main story, and this is not a game where there are additional resources or means to get past this content.

You also need to decide what does the endcap of general play look like? What I mean is that there has to be a progression point that you expect anyone who is playing your game can reach. Can they beat every ultra-hard content, do PvP, see the story to its conclusion, and so on. The reason why this is important is that all the rewards and other modes in your game must be balanced to give players the ability to make this progress. If you want to have whale-level content, you need to set a hard line as to “this is what everyone can get to and enjoy” and “this is for the people who want to really show off.”

At some point, in every live service game you are going to reach a stage with your content that a portion of it is “done”: this experience will be the same for every player no matter when they joined and there is no reason to update or rebalance it. Still, if we’re talking about a game with years of content and updates, it may be required to make a massive change at some point — this is what MCoC has done with acts 1-5 with their reward structure.

With the three types of players in a live service game — the casual, core, and hardcore, your goal is to get casual players to become core players as easily and as pain free as possible. For people who want to take that next step into hardcore territory, there must be a means through progression to make that outside of a battle of credit cards. If core players see that the only way to keep progressing is to spend money not by choice, they are going to quit your game in droves. If you decide to increase or add more to the progression over the course of the game, then you will need to update the rewards that go with your content.

Balancing characters in live service can be a nightmare and always presents the issue of having someone be forever good, or have an expiration date. (source: Limbus Wiki)

One important detail for character-driven games, if you update characters or balance them after release, you must make sure that they are still viable for the content in your game. Beware of making blanket changes to your characters, especially for PvP or PvE games where players are supposed to fight against other characters that they can collect. This goes back to the fact of locking down content and making sure that nothing affects them in terms of rebalancing, as you don’t want to make content for casual players impossibly difficult because one of the fights has been made much harder. However, and this is a big one, if we’re talking about games that once again reach years of content and updates, just by the very nature of your design, older characters will not be as viable as newer ones.

This is an interesting challenge of MCoC, that now has over 300 characters in the game since its inception. While there are some characters who never fell off in terms of power and utility, a lot of the older characters are definitely lacking in terms of their modern counterparts. Here’s an example of how two characters could work between older and newer design–

- Old character — attacks have a 50% to cause bleed each hit.

- New character — attacks guarantee to do bleed damage each hit. Hitting with a medium multiplies damage of bleed. At 20 stacks of bleed on the opponent, the character becomes unblockable for 5 seconds.

What the developers have been doing is slowly going back over their back catalog to review and rebalance older characters to bring them up to par with the newer ones. In some cases, the older characters are now even better in some respects than their newer contemporaries. Whereas Arknights handles their balancing a bit differently. Six-star characters usually have something unique in their kit that is not repeated with other characters of the same class to keep their utility up. For older characters, modules are introduced over time that provide an additional progression and upgrade state for them.

With the reward structure of your game, another common practice is to purposely split resources and rewards to different modes — if the player wants to grow, they need to do modes A, B, C and D to gather all the resources. While this can work if the content is similar — story modes, story challenges, etc.- you don’t want to be mixing different modes — PvP, Guild, story, hardcore, etc. There are people who will gravitate towards one or two ways of playing your game: maybe they only care about PvP, maybe they just want to do the story. Forcing them to engage with guilds or other content that doesn’t interest them is an easy way to get them to quit playing. You can make it easier to get resources in certain modes, but you don’t want to only have them as the way to get something.

And remember this point about content — no matter how challenging you make it, how long it is, how long you spent developing it, there will be people who will finish it day one of its release and then ask for more.

Creating Content

For the final point of this piece, I want to focus on the actual decision making to add new content. Your ability to create something new is going to be limited by the design and scope of your game. If you’re making an FPS multiplayer game, you obviously can’t add in a real-time strategy mode.

What you want to look at are ways of tilting certain aspects of your game into different ways of playing. With Arknights, new modes that were added still involve the tower defense gameplay but change things up with having meta progression and challenges that aren’t featured in the story content. Returning to MCoC, their biggest update in terms of a new mode was the introduction of their Battlegrounds PvP mode, but once again, they also introduce new end-game challenges from time-to-time.

what is the killer for many live service games is when they try to coast on their content for months on end and only focus on the purchaseables (source:Nox)

As I’ve said throughout this piece, you cannot just stay with what you have and expect people to keep playing for years on end. With limited-time content, this also gives you a chance to get public feedback on a new mode or type of play. You may find that your community loves content like X, and maybe you can develop more of that.

Live service design is very much like having to scoop water out of a sinking boat — you’re never going to reach a point where you can say, “this is finished.” The only time when that is acceptable is if you are moving on to a sequel or the game has gone end of service or EOS. For every dollar that comes in from sales, cosmetics, banners, etc., that is going to have to go towards new content generation, as without it, that money will disappear quickly.

Taking the Good with the Bad

Live service design has always been a double-edged sword — when it works, it can lead to a studio defining title that can keep them going for years. The best examples of live service can easily pull in 50 million a month or more.

But this is a tough-as-nails genre to work in and requires a studio to understand live service design, production, and planning. You do not jump into making a live service game without already thinking about the next six months to a year’s worth of support and updates. People need to know that you have a plan for developing a game, and if you don’t, they are going to leave in droves. It is very rare to see a live service game on death’s door bounce back, and I honestly can’t think of any that were able to completely turn things around.

With that point, there is one major painful truth that you also need to understand, just as you must come with a plan for future content in a game, you must also have your monetization locked down from day one. What has also been the killer for live service games is when the developers change the pricing of content to make it more expensive or introduce additional monetizations on top of what’s already there, twisting the knife further by not releasing new playable content while making these changes.

And we are still waiting for another live service game to move things forward as much as Genshin Impact did, and whether or not there is still room in the space for a new game to thrive.

For more about live service design, be sure to pick up my book on the genre available everywhere.