Micro transactions and DLC in game design are two of the big changes over the last decade. For some, it’s the wave of the future and a changing of the times. For others, its evil incarnate and will ruin the industry forever.

Regardless of your opinion, they are here to stay. In the past I’ve talked about the balancing issues that have to be taken when designing games built around micro transactions. For today, I want to talk about the right and wrong ways to try to convince people to actually buy them in the first place.

Making Life Easier:

For this 2 part post, we’re going to categorize micro transactions into three groups:

Quality of Life: Purchases that do not add any new content to the game, but simply make the game easier or more efficient to play. Examples: Experience boosters, in game currency, additional stashes, character slots, etc.

Vanity: Purchases that add aesthetic or flavor items to the player’s account. These options once again have no affect on content or actually playing the game. Examples: Pets, costumes, color changes, etc.

Content: Purchases that directly add to either the gameplay or content of the title. Examples: New weapons, Quests, etc.

We’re going to ignore micro transactions based on in game currency for this post, as the focus is on convincing people to spend additional cash on your title.

Let’s start at the top with quality of life. QoL items can mean a lot of things based on the title’s design. When subscription based games move to a F2P format, usually the first thing that is changed is the addition of QoL purchases. This is usually done by looking at the original content and finding areas that can be trimmed down for people to buy back later on.

It’s important to realize that creating QoL purchases is a slippery slope and restricting too much can make it seem like you are holding features at hostage from the player.

It’s important to give the players a quality product first, micro transaction second.

One of the craziest examples of this would be from Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, where Bioware actually removed the ability for a character to sprint if they played the game in F2P mode.

Most examples of QoL purchases aren’t as extreme, such as more inventory space or character slots. As long as the player has enough to play the game the way it was meant to be then it’s alright to have these as bonus options for the hardcore players.

Another area that you want to avoid with QoL purchases is forcing issues onto free players that a paying player would not have to deal with. In DC Universe Online, free players had an actual limit on how much in game money they could carry at one time. This required them to hoard items they wanted to sell as to not lose money when they went to sell them.

There needs to be a careful balance with QoL items: You want to restrict the player enough so that the option to buy more would be utilized, but not restrictive enough to make the game appear poorly designed without them.

Style Points:

Moving on let’s talk about vanity items. Vanity items are by design the easiest, as there is no need for altering the game balance to have them. Their worth is based largely on the quality of the vanity item. A simple color palette change isn’t as impressive as a full on costume change for the character.

Pets, animation flourishes, capes, the only limit on vanity items is the one set by the team. Two examples of great vanity item design would be from League of Legends and Path of Exile.

In LoL, every character has alternate costumes that can be bought using real cash. As time went on, besides designing simple skins for their champions, Riot introduced premium skins. These costumes cost more money than the average skin, but not only redesigned how the character looks, but added new sound effects and graphics to them.

While in Path of Exile, there are pets, animations and actual spell graphic effects on sale.

The graphic effects basically change how the specific spell would look when used in combat. A fireball may be replaced by a dragon made out of fire for example.

Now the only thing to remember is that you have to be careful when it comes to pricing vanity items. Obviously you want to earn back the time and money spent on creating them in the first place, but you can’t be greedy.

With League of Legends, Riot specifically split regular and custom skins by pricing to offer different price points. Obviously, the premium skins look better, but cost much more than a regular skin. By having different price points, it allows consumers to buy content of varying prices instead of nothing but expensive items.

No matter how fancy or beautiful you make a vanity item, they are still just aesthetic changes and nowhere as important as our last category: gameplay.

Making a Good Thing Better:

Lastly we have the gameplay category and where things get complicated. Gameplay is a variable term and can mean anything from a new raid in a MMO, to a four hour side story in a single player campaign.

Of the three categories, gameplay can be the most polarizing sell to gamers. Some see it as selling expansion pack content in bits and pieces, while others view it as the designer cutting out gameplay to be sold later for more money.

The first challenge of listing any gameplay options for sale is overcoming those preconceived notions. Day one DLC or on the disc DLC are very hard sales as they are perceived the most as cash grabs, while future DLC packs or monthly content are viewed more favorably.

The biggest thing as a designer is to make sure that the base game has enough content for what is typical of the genre. If a regular game takes about 8 hours to complete, releasing one that only takes 4 hours with multiple DLC episodes is not good.

Another major decision regarding adding gameplay content is: at what part does it take place? With the Deus Ex: Human Revolution DLC, the actual episode takes place around the half way point of the campaign. While the Borderlands 2 DLC episodes range from a quarter of the way through, to after beating the main quest once.

This is dependent on your long term strategy, as you want to give players more things to do, but it may be a harder sale to introduce content so far into the game. But on the other hand, expert players may not want to buy content that won’t aid their current characters.

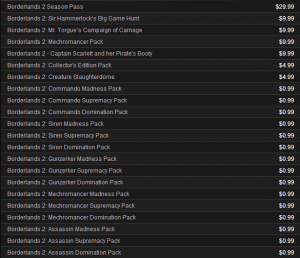

Gearbox planned for DLC episodes for Borderlands 2 for several months. Providing more challenges without skimping on the original content.

Regarding actual items, its common knowledge that player’s don’t like games where they are forced to spend money to compete.

The quicker your title becomes “pay to win”, the faster people will stop playing.

It’s important to give the players a quality product first, micro transaction second. As gamers are more willing to spend money on a product they find well done in the first place, not to fix what the designer’s left out.

So, now that you have your content, how exactly are you going to put it out there for gamers to buy? Convincing gamers to fully embrace your DLC requires more than just putting out content, you have to sell it and there is one studio that has definitely made a killing out of that.

Come back tomorrow for part 2: Where I’ll be talking about how to show off all that lovely DLC.