It’s a new year and that means it’s time to once again ponder the nature of game design. Given all the YouTubers, streamers, and now even professors teaching design, you may think that the act of studying games has become an exact science. But maybe it’s because I’m not actively searching for them, but I’ve yet to see someone talk critically about the nature of game design that avoids the trap of basing every examination from only their point of view. There’s nothing wrong with having an opinion, but I’ve come to believe that there is more to talking critically about game design than just saying “this game is good/bad.”

Does the Past Hold Up?

A point that I feel is lost on many people who play/study games is an obsessive holding on to the past. Even with my design videos and books, I quite frequently cite the major names of a genre — Doom, Mario, Halo, FTL, and many more.

If you go on social media, it’s common to hear from people over the course of 2024, especially content creators, saying that there weren’t any good games released, or that they miss the good old days. In several of my design books, a common complaint is when I don’t spend enough time analyzing a game like Half-Life or Super Mario World.

Where I would argue with people who hold on tightly to the past is that game design is a constantly iterative and evolving market. Every new game is like throwing a rock into a pond — with those ripples leading to new designs and even new sub genres.

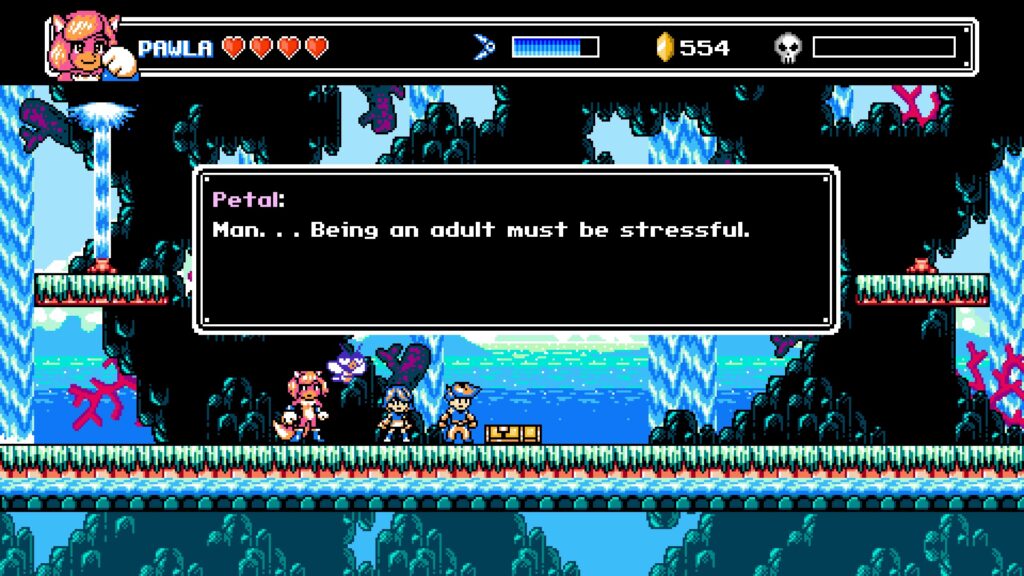

games like Fallen Leaf are designed to emulate classic experiences, but avoid the pain points associated with them (source: Author)

A common trap for designers is using the past as gospel for the future — that the old games should be copied as close to 100% as possible, and that the developers got it all right back then.

What people tend to misconstrue is that those “classic” games were the future of that time. Super Mario World was to platformers what games like FTL, Darkest Dungeon, Balatro, and many more are to their respective genres today.

I’ve said this line before — classic games are the benchmarks that must be cleared, not the goalposts for your game.

Wise developers who want to make a game like in the past will go beyond in some respect — the save system is fairer, auto-mapping, better onboarding, etc. When interviewing developers who have made modern retro titles, one of my favorite comments from them was that they wanted to make a game like their childhood, however, they wanted to imagine what it would have been like to iterate on that design — so that someone who wasn’t around in 1989 or 1991 could have an appreciation for it, and still be able to figure it out.

Many classic games are, to be bluntly, failures when it comes to UI/UX. I want to be clear that it’s not the fault of the designers, but just the nature of something produced early in the history of an industry vs. further into that industry’s development. And being able to study design, not just yelling that a game is great/stupid, is still something that needs more work done with.

Game Design Studying

I’ve been talking about this next point for almost a decade now — There needs to be a formal appreciation and methodology for game design as its own unique field. Game development is different from game design, nor is learning programming or art going to prepare you for designing a game’s systems.

What has been the problem with this approach is that no one has yet to figure out a standard way of studying a game. Some might say you need to read books by experts, others may say to keep playing videogames or only playing the best videogames.

Both have their downsides. Books are time-locked to when they were published. My first two design books on platformers and horror already feel dated by all the newer takes that were released after. You can’t just study what videogames were like in insert year here and then go out and make a game that will do well today. I return to my conversation I had with Rami Ismail when he told me about how hard it is to give advice to people about being successful in the industry. Any game that sold well in the past, if you try to remake that same game lock, stock, and barrel today, it will fail. The reason why is that people have already played that, why would they spend money to play a game they’ve already done?

For the second half, just playing videogames day in and day out is not the same as examining them. I’ve talked plenty of times in the past about how I didn’t really start to study games until 2012; all the years prior playing games meant nothing. This is why when I replay classic games today, I have a newfound insight and appreciation for them that wouldn’t have been possible to examine back then.

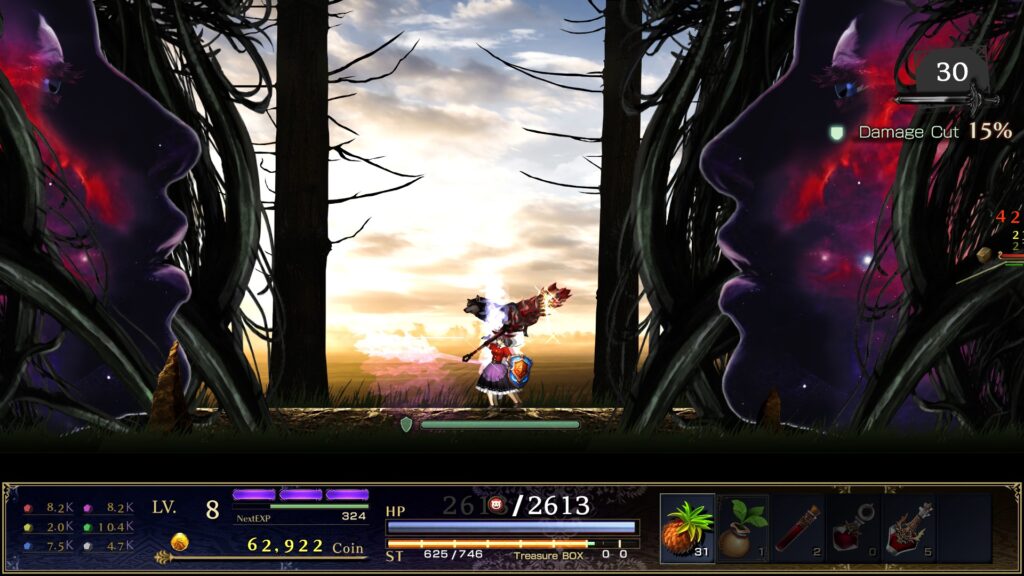

Being able to study design is about looking at all varieties of games and understanding what the intent of the designer was (source: Author)

You can’t just play the games that everyone else is playing. One, you’re getting a heavily curated experience and a game that has been polished so much, you’re not going to easily spot pain points with the genre itself. And two, only playing popular games is what leads to only playing a few games each year. For me, I’ve played over 1,000 games in 2024, over 200 that came out that year.

If you want to be able to study design, and study it effectively, you need a bit of both. First, understanding the methodology and philosophy of a game genre, and then examining how a game works within the definitions of said genre. Being able to see why something works/didn’t work in one example will help you understand how it can be used in other games. And with that, it’s time to talk about why there is a difference between a good game and a successful one.

What is a Good Game?

I’ve long since stopped worrying about being a game reviewer. I don’t care about assigning a score to a game, appeasing fans or being ammo for trolls. What I try to do is to examine whether the game was “good.”

When I take apart a game, my goal is to figure out what the intent was by the developer for their experience, and whether the game mechanics meet, beat, or fail, in that regard. This is how I can come up with very polarizing opinions when I study famous games — I can find something amazing in a game that everyone has written off; I can find a huge problem in a game that everyone has declared as their own personal best game of the year.

A crucial aspect of game design analysis is being able to pick apart sequels to figure out what’s new, what’s the same, etc. (Source: Author)

The advantage of this is that I can get away from just stating subjective information and saying that if I liked/dislike the game, then it must be a good/bad game. It’s also why I can fully recommend a game that I hated, and I can argue points against a game I loved.

Being able to look at a game critically and objectively is something that more people claim that they are expects or reviewers need to do. Being able to do so will allow you to start thinking about the next, and even more important point.

What is a Successful Game?

Now we come to the point that isn’t discussed as much when it comes to game design and game development — did a game succeed? This is very much uncharted water for people who cover the game industry and study design. Returning to the previous section — a good reviewer/critic can talk about whether a game worked or didn’t work, and a lesser one can at least explain why they personally liked or disliked it, but it’s another matter entirely to try and figure out if a game succeeded.

You can have a game-of-the-year winning title, one that is universally loved by critics, sold millions of copies, people who played it can’t stop talking about it, and it still failed. The challenge is figuring this out, and more importantly — what do you take away from that game when you are building your next one?

I’ve said this plenty of times before — copies sold do not in any way measure the success of a game. That line may be a bit hypocritical: If I just said that a game sold millions of copies and is universally loved by hardcore fans, how did that game fail?

That, my friends, takes us to the one true judge of a game, more important than any reviewer, critic, analyst, website, or award body: the churn rate for that game. If a game sold one million copies, however, only 100,000 people played it for more than 30 minutes. I can assure you with every fiber of my being that the next game from that studio is not going to be another million-copy seller or anywhere close to a million. By contrast, if a game only sold 10,000 copies, but 9,000 of those players saw it through to the end, that developer is in a good spot for their next game.

It’s at this point that we start to take a closer look at the mechanics of the game, and the user experience of playing it. What is keeping people engaged? What’s stopping them, was there a major point when the game just fell apart for many people?

If you don’t learn this and are unable to take an impartial view of your game, then you are going to be firing blindly in the dark for your next title. And worse, you are going to find that your games are getting you diminishing returns, and if you continue to invest the same amount of money and resources, or more, into that concept, you can easily burn through all the profit that is sustaining your studio. This is a problem that doesn’t always make itself known immediately, but upon reflection, you can see the telltale signs:

Game 1 does really well and sets the studio up for success, game 2 is made to be bigger or more advanced compared to game 1 and doesn’t even come close. Game 3 is an attempt at a course correction, but it’s too late and the studio doesn’t have the finances to keep going.

Mimimi Games sadly closed in 2024 despite having a breakout success, but struggled to grow and retain an audience from game to game (source Steam)

The difference between a good game and a successful one is that the successful one provides growth for the studio — be it in the form of money, new fans, or ideally both. You can keep putting out good games that meet your metrics for success, but if you’re not retaining or growing your fans and consumers, you will be on borrowed time. There’s nothing wrong with having a niche success, there have been plenty of games that have become beloved by fans who know that this game is never going to reach the top 10 list in any year. But it is important to go into the development and budgeting of said game with the understanding that you shouldn’t be investing millions of dollars in it, a point that I will return to in the next section.

I’ve lost count of the number of studios I’ve seen over the 2010’s who have one amazing game, to then close a few years after.

Sustainability

In the 2010’s, one of my most repeated phrases was talking about variance and RNG in terms of gameplay and replayability. For the 2020’s, the new game industry phrase is “sustainability.” Given the horrid year of layoffs and studio closings of 2024, sustainability is more important than ever to understand as a designer and studio.

From the outside, it’s easy to view game design and game dev under the same high-pressure lense of other businesses — it’s all about that one product that’s going to make your company millions and do anything you can to get it done.

Game design and studio health is not about one game but creating a portfolio of quality titles that make people excited about what you’re doing next. The failure of big business investors like the Embracer Group was treating game dev like any other business. There is no studio alive today that can create high-quality hugely profitable games guaranteed every year. Likewise, studios are not interchangeable — telling an RPG studio that they must develop a reflex-driven high-octane action game is not going to work.

There is another side to this as well — understanding how much should go into a single game. The 2010’s was a period where many developers who entered the indie space focused on “the dream game”; no matter how long it would take, how much money it would cost — the goal was to make that one game. Part of being sustainable in the industry is understanding that one game should not be the next 5-10 years of your life and for a studio to be sustainable, knowing just how much to invest in a single idea.

Being sustainable is about understanding the kind of game you want to make and the scope and audience for it, and Strange Scaffold has been doing well in this regard (source: Steam pages)

You can throw infinite dollars at a game concept, but at some point, the amount of time and money spent is not going to continue improving on it, and there’s very little chance that the game will earn a profit. The consumer is not interested in your 500+ hour slog of a game with every single mechanic and game system one could imagine; they want a memorable and polished experience they haven’t seen before.

For every developer that you hear about from major news sites and influencers, there are hundreds of equally deserving games that never get mentioned. You cannot put all your hopes and dreams on your game being randomly discovered one day to amazing success.

The Formula vs. “The Formula”

One of the more frustrating parts of looking up game design theory and discussions online is that everyone has “the formula” — a game must be like this, all videogames are X, this is the best way to design Y, etc. What we’ve seen over the 2010’s through today is a complete denouncement over what a game “must” be. Pick any genre out there, and you will find examples that hold to those standards, break those standards, or invent entirely new standards…to then break.

Returning to the original point of this post, it’s one of the reasons why it’s hard to come up with any kind of standard of game design, but I do feel that it is possible. Returning to an earlier post, I said that every genre has inalienable elements that are the backbones of that respective gameplay. Take those away, and you don’t have a game that represents that particular genre.

I can talk all day long about what makes a good platformer, shooter, strategy, horror, etc., and I’ve written books to that point. What I can’t tell you, and what no one can tell you, is what should be built off those foundational elements. This is where the concept of game feel comes in — you can watch or read a tutorial that tells you how to make a character jump, or a gun shoot; but that doesn’t inform you about whether your mechanics feel right to the player.

Game mechanics and systems are not interchangeable — you can’t just take something you liked in one game and copy and paste it exactly into your game. You must understand how it was implemented and what it impacts from a design perspective. And remember, just copying the big-name game of the year verbatim is not how you will grow as a designer. If you can’t answer the question of what makes your game interesting to play, the consumer is not going to do it for you.

Beginning 2025

2024 was a great year for finding new and exciting games, but a terrible year for the state of gamedev. I’m a broken record at this point, but I’m hoping that we would be seeing some kind of movement in terms of further legitimizing game dev unions and raising the discourse on studying game design.

Gamedev continues to be a mystery for a lot of people, and it’s important to educate people on the mistakes and issues that can come up before they start working on a project. I’m always available for consulting and work, but the industry needs to do better than just having a “learning by doing” learning process, especially when people are putting their livelihoods on the line.

If you enjoyed my piece and want to follow me, I’m posting on Bluesky and you can find links to all my other works from there.