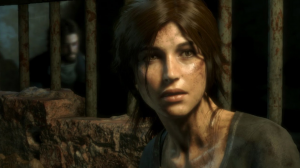

I’ve been playing through Rise of the Tomb Raider lately. Going through it, I’m finding myself in the same position as the first game: Liking it, but not loving it. And one of the major reasons is how the game fails to balance the gameplay with the story they want to tell. For today’s post, I want to expand on this clash between gameplay vs. story and how it created a ludonarrative dissonance.

Story vs. Gameplay

Video games have always been a constant balance between what you want the player to do vs. the story you’re trying to tell. For a lot of video games, story is either the main focus (Narrative Games, RPGs, etc) or merely serves as the backdrop (XCOM, Mario, etc). Lately, we have seen developers try to combine the two and present a story that infers on the gameplay and situation.

Series like Uncharted, The Last of Us and Tomb Raider attempt to integrate their story into the mechanics and situation.

In a recent post, I talked about the difficulty of adapting video games to other mediums. One of the key points was the fact that you cannot translate gameplay into another medium. The problem with Tomb Raider and the latest iteration of Lara Croft is that they’ve failed to balance the gameplay with the story.

Serial Raiding:

Lara Croft in both of the latest Tomb Raider games was presented as still new to her profession. The first game was a trial by fire and Rise of the Tomb Raider is her first big quest. The story of the game attempts to make us resonate with Lara with how she responds to the situations.

She is someone who is trying to be tough in these extreme scenarios, but shows emotion and questions herself at her breaking point. The cutscenes paint her has someone who is struggling to deal with the suicide of her father and if she’s really able to keep going and trust people.

The problem is that Lara is definitely not the same Lara we’re playing as. In the first game, there is a huge emotional scene when she first takes a life in the jungle.

From that point on, she shows no problems with shooting people in the head, slicing throats open and more.

With the second game, there are cutscenes that show her distrusting of new people and having to be forced to work with them, but then in the field, she accepts every quest by saying something to the effect of , “I’ll do everything I can to help you no matter what.”

This wouldn’t be seen as a problem in other games where the story merely sets up the situation. However, as developers are trying to integrate the story into the mechanics, it creates these multiple personality issues.

Balancing Gameplay:

There are two counterexamples I want to talk about. The first is the Batman Arkham series and how they presented Batman. Batman is always shown as a bad-ass and in control at all times kind of person. The series doesn’t try to tone him down or contradict his background.

In each game, Batman can handle any person in one-to-one combat or a group in hand-to-hand. Where he suffers is with fighting multiple armed thugs at the same time. What the developers did was use that to enhance the mechanics with the “predator”-styled gameplay. During those sections, the player has to figure out how to take out a group one person at a time. This way, the story/character is in sync with the gameplay of the title.

The other example would be from Hotline Miami 2. One of the characters in the game is a journalist who doesn’t want to kill people. At the start of his stages, he will refuse to use guns and only incapacitates. If you push him enough, he will snap and go into a rage where he will start killing people. By doing this, the game gives us a character with a different personality and integrates it into the mechanics.

Fitting Everything In:

When the story doesn’t mesh with the gameplay, it can present a disjointed game. We’ve talked about the idea of harmonizing game design and how everything is in sync with each other. Sometimes you can’t have it both ways with having a relate-able character that also attacks like a serial killer.

The games that work the best are ones that either leave the story as the setting, or are more careful with the balance. Avoiding ludonarrative dissonance may not be high priority when designing a game, but it’s one of those elements that feel out of place in great games.

Thanks for reading this post. You can find me on Twitter for daily updates on all new posts and nightly streams on Twitch around 10 est. Check out my YouTube Channel, now over 1,000 subs strong, for daily videos on game dev topics and video games. Finally, check out the Patreon campaign for ways to support everything that I do.