In a recent developer diary entry, later followed by an interview, I discussed the concept of “walkers” in city-building games, and how Tilted Mill’s forthcoming game, Medieval Mayor, would use walker-based systems. To some this was welcome news… to others, cause for concern. Later, in an email conversation with Josh Bycer, I found myself expounding, on this complicated and perhaps misunderstood area of city-building game design. How could such a seemingly narrow subject be the source of such heated debate?

A Moving Conversation:

Many players have commented that the walker systems of games like Caesar III and Pharaoh were unrealistic, to say the least, and that they forced players to lay out roads and intersections in unrealistic ways. Though technically you weren’t forced to do this, it was the best way to maximize results (and for many players, particularly advanced players, this is forcing you, and I would not argue with that perspective!).

Other players are simply confused and frustrated by “dumb” walkers – walkers who don’t go where you need them, and often go precisely where you don’t need them. Why on earth should an actor visit a clay pit anyway?

In real life people generally have a destination in mind, and as a real-life road planner your goal would be to enable them to get where they want to go, so more roads and intersections are a benefit. But with thoughtless random walkers the opposite is true. Instead, long straight roads with few intersections are beneficial because this prevents these walkers from wandering off where you don’t want them to go.

“Actually it’s not so much dumb as it is random (and there is a difference).

The walkers are not making bad decisions – they’re not making decisions at all.”

Of course, many of the millions of players of these games don’t even notice any of this or care. And for many them Zeus or Pharaoh remains their favorite city-building game.

A lot of players (including me, for what it’s worth) play those games more like this: fires keep breaking out over there, I slap a firehouse in that area, soon the fires subside… it’s all good. I don’t need to know exactly what’s going on or how those walkers may wander around…

It’s worth noting that the resource storage and distribution component of the walker system in Pharaoh, Zeus and Caesar III was destination-based, not thoughtless or random (excluding the bazaar/market lady who delivered to houses en masse and thoughtlessly). Delivery people knew exactly where they were going. All we’re talking about here are walkers providing stuff housing – but that’s a huge, critical aspect of city-building gameplay!

My intention here is to lay out some thoughts about this area of city-building game design, developed over many years of making these games. We take this stuff very seriously. We listen to (and generally agree with) most observations, if not necessarily all conclusions, on both sides of the “walker question” (and many others, for that matter).

Some Perspective

City-building games are meant to model the process of designing and building a city – not a nation or an empire, not a small town or base. City-building is not about managing the lives of a bunch of sims. This perspective is critical, as it relates both to the scale of what the game is intended to model as well as your position in the game as a player.

In a city-building game we can’t directly represent every member of the populace visually – there are far too many of them. But we still want to see enough people that it feels like we are. We can’t abstract the population into a simple number or slider, as in, say, an empire building game, and there too many people to treat in detail as in, say, an rpg or shooter.

In city-building we walk a very fine and very difficult line in terms of scale. We want a city with 500,000 people but we can’t have tens of thousands of houses on the map, or hundreds of thousands of figures walking around.

In fact, anything more than a tiny fraction of that is way too much for players (and their systems) to contend with.

But we still want LOTS of people moving around the city. We want enough people so it feels like a city, so there is a flow, a sense of numberlessness. We want a feeling of numberlessness where you can also tell who everyone is and what s/he is doing – that is a big challenge!!

The ratio of houses to non-houses is also important. In city-building games you tend to have many houses vs. fewer “service” buildings (such as a theaters, markets, etc., which provide things to houses). This asymmetry is because the core gameplay of most city building games is about providing specific stuff to relatively generic houses. You may have as many service buildings overall as houses, but this is not really relevant because there is much more variety there.

“The goal is to get houses to have lots of different services like theater, and your primary limitations are map real estate, building cost and workers.

This is a “push” system – houses don’t look to see what’s near them – it’s done the other way around.”

For example, in a fledgling city (or a subsection of a developed city) you might have 20 houses to 1 theater, 1 market, 1 fire station, and so on. As a player, you treat housing en masse, not quite globally, but still somewhat generically, as a whole body.

This is why in many games housing is painted, not placed individually. In fact technically you’re not even BUILDING housing at all – you’re designating a housing area. That’s how generic it is. It’s an empty shell.

It’s also why housing evolves. It’s like planting a crop, then providing the various elements like food, water, sunlight. That’s the basic gameplay for a traditional city-building game. The character, interest and diversity are on the non-housing side not the housing or citizen side.

Radius Maximus

In early city-building games we employed a pretty simple radius effect system. You place a theater, it radiates “theater”, and every house within a certain radius of it “has theater.” The goal is to get houses to have lots of different services like theater, and your primary limitations are map real estate, building cost and workers. This is a “push” system – houses don’t look to see what’s near them – it’s done the other way around.

This approach has also been used in a lot of combat rts games, and all sorts of games, in fact. It is very intuitive to players. It’s also very straightforward to communicate visually and instantaneously to players, which is critical for real time strategy games (including and especially real time city-building games).

The radius system models whether each house is close enough to a theater (to theoretically visit it once and a while), but because of the ratio of houses to theater, it’s much easier to view this by looking at the single theater’s radius of effect and seeing how many, and which houses are within it.

The challenge of completing large scale projects while keeping your city in check has always been a major pull for city-building fans.

The radius scheme makes for a very playable game. It’s a simple way to model city-building and to give the player clear visual information about what’s going on.

It easily supports populations as large as you want, because this is completely abstracted. Overlays show what the different service buildings are affecting, some number on the dashboard shows your population, and a single house may actually contain 500 people.

A lot can be done to make this type of game more visually appealing and engaging, but that’s not the same as feeling like you’re building a living city, with organic connections made by people actually walking around. The radius system also requires a two step process to see what’s going on, via special overlay displays.

Introducing… the Walker

With walkers providing services and other things to housing you’re looking right at the game’s actual systems, what the game is actually doing. Watching people walking from one building to another, along roads, shows you the important connections in the city, in a fun and engaging way. Real people walking around doing real things – and therein lies the dilemma… if these are actual people doing real things, shouldn’t they be citizens coming from houses and getting what they need, as in real life?

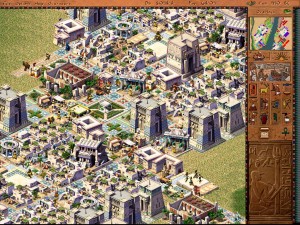

Pharaoh was one of the first examples of the walker system: As citizens provided food and services to the houses they walked past.

That is more realistic and therefore more intuitive. But as we’ll see it’s less communicative about what’s actually happening in the city.

It also clashes with the scale of populations in city-building games, and with the asymmetrical number relationship of housing vs. non-housing.

Who’s Who and What’s What?

With a push-based system (actor delivers theater to housing) you can see exactly what is happening just by looking at the people and buildings on the screen. If you see an actor, that means “theater is emanating from somewhere.” He’s carrying theater around with him. He’s conveying theater. He walks past a house that means the house just got some theater. You see the house change graphically as the actor walked by, that happened because it just got theater.

If that didn’t happen that means the house didn’t need theater (either already has it, or needs something else first). That’s a lot of great information delivered in a fun and engaging way, because on top of that the actor has a distinct and fun character. Special overlay views and filters still allow you to hide distracting information when necessary, and give more detail.

By contrast, in a “realistic” pull system (citizens come from houses and visit the theater) all you would see, all the time, are generic, identical citizens walking around. Any visual difference among them is largely cosmetic, and does not effectively communicate the important stuff like, how close is this person’s house to a theater?

You would have no idea where these citizens came from or where they were going, or what benefit they were providing to which home or segment of the population. They communicate basically nothing about the interconnections in the city or THE THINGS YOU NEED TO DO, for example, “I need another theater in this area”.

Mass Effect

Push systems also work well because a single figure from a service building (e.g. an actor) can affect a huge number of houses on a single trip, almost simultaneously, vs. needing one figure per house per service.

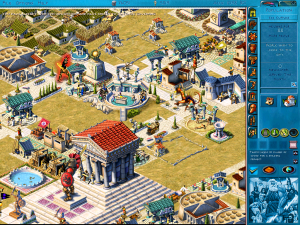

Children of the Nile‘s use of a pull system works out due to having lower populations of people compared to other city builders.

It is very gratifying to see a whole block of houses suddenly pop up a level because you just plunked down a theater and fed them what they needed, especially when housing evolution is the main point of city development.

It’s gamey, it’s unrealistic, and it’s gratifyingly fun. You place a service building to serve an area of housing, to apply some effect to it.

Scale Matters

Push systems suit the scale of city-building better overall. A more realistic “get” or “pull” system works perfectly when you only care about one person or one family, and when you, the player, are identified with them (or him/her). This is very intuitive. It’s not abstract at all. Those are big advantages in terms of making the game immediately graspable and enjoyable.

But that is also a different type of game. Even if you could truly do this with 10,000 “people” it would probably only be fun for a few minutes. Or the fun would be different (it would be fun to be able to spy on people’s lives, not build a city). If you click on a random guy and he reveals all this great info about his life, that might be fun in some kind of way, but is not great city-building gaming, to me.

With push walker systems you are also able to present to the player a more easily digestible set of interesting and distinct characters, vs. thousands of realistic, subtly different citizens. So you have the butcher, the miner, the actor, the gladiator, etc. vs. “the guy who lives over there.”

Random Seems Dumb

Push-based walker systems are obviously not without their problems – the main one being that the system is usually dumb. Actually it’s not so much dumb as it is random (and there is a difference). The walkers are not making bad decisions – they’re not making decisions at all.

You place a theater and expect it to affect all nearby houses – but the actor repeatedly takes off in the wrong direction (or turns the wrong way at an intersection) and houses very close to the theater chronically fail to get theater. This can be frustrating, especially if the actor’s wrong turns keep taking him to where there are NO houses. It can seem nonsensical that houses are still saying they need a theater when you just built one right near them. What are you supposed to do, build another one? That didn’t work the first time!

On top of all that, since the medium carrying the theater effect is a person “he” (and therefore the game) looks like it’s behaving unintelligently much more than it would if, say, this were a game about ping pong balls. It looks like “he” is not doing what “he” should, or what a real person would do, or what I, the player, who made him, want him to do.

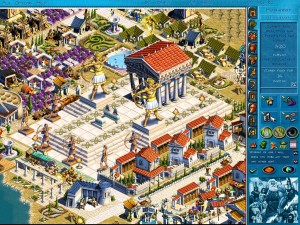

On the other hand, Zeus’s gameplay would not work with a pull system due to the population’s representation being abstracted.

Players naturally and understandably tend to think that these are like the real people you see walking around a city or town (i.e. citizens purposefully doing their jobs).

But of course we don’t want players to think of walkers like they’re ping pong balls. We want them to seem like people…

Smart Walkers

So what about making the push walkers smart? That is not as easy as it seems. There are far too many cases where we (as AI designers) cannot know what a given player wants to happen, expects the walker to do under a certain conditions, etc. And as soon as we start trying to make the walkers smart they end up seeming dumber and more irritating, because now they’re doing the wrong thing ON PURPOSE. At least with random walkers + roads + roadblocks you have some sense of control!

The Perfect Push?

A perfect push system would probably be something like flood filling roads radiating out from a service building, sort of like having walkers that divide and clone at every intersection (and this type of system could in fact be represented by walkers). This has been done. It is very playable… and almost takes us back to the old radius approach… but perhaps sacrifices too much of the fun and organic, living nature of the walkers.

“With push walker systems you are also able to present to the player a more easily digestible set of interesting and distinct characters, vs. thousands of realistic, subtly different citizens.

So you have the butcher, the miner, the actor, the gladiator, etc. vs. “the guy who lives over there.” “

What Does it all Mean?

With all the problems of the old walker-based random dumb push systems, those games are a lot of fun, and a unique kind of fun, loved by millions of people. Those walkers were frustrating. Fun, frustrating and irritating for many players, but those systems present the feeling of building a big living thing, the city as the organism pretty well.

This is not an argument for old school walker systems in their exact original form. But it is an attempt to explain some of the benefits of that approach, why the most obvious or “realistic” approach doesn’t work as well as it seems like it should, and a bit about what we’re doing in Medieval Mayor.

Medieval Mayor

In Medieval Mayor we have in fact come up with… something new! Not entirely new, of course, because it is quite well-informed by experience. We think it’s really cool. We don’t want to say too much about the nuts and bolts before players have a chance to really experience it more, because this is such a difficult subject to deal with in words.

What I can say is that core city systems are carried out by people walking the streets, so roads are your main tool to connect buildings, and the people on the streets are your main feedback about what’s happening, because they are what’s happening. But unlike in, say, CotN or Hinterland (or Zoo Tycoon for that matter), the figures walking around are not a one to one representation of the population. There are a lot more people in the city (in terms of consumption, employment, labor, tax paying, etc.) than you ever see on the screen at one time.

Finally, despite the critical importance of walker systems, there is obviously a lot more to “classic city-building” than this! Many people reading this (those that have made it this far) probably don’t think about this stuff so much because we take it for granted (you know, big scenario goals, winning and losing, requests and events, that kind of thing).

But a whole generation of players who have only played much simpler city-building games, or who have never played city-building games at all… or have only dabbled… or maybe forgot what real city-building is… are largely unfamiliar with that stuff in the context of city-building at least. That’s the stuff that really drives the game, gives you something to do with your city, some purpose for it! We’re extremely excited to be working on Medieval Mayor and hope and believe it will deliver everything city-building fans crave.

-Chris Beatrice

About Chris Beatrice

Chris Beatrice is a veteran game developer with over 40 (and counting) released titles under his belt. Chris has been making city-building games since almost before there were city-building games. His lead design credits include Pharaoh, Zeus, Children of the Nile and SimCity Societies. In 2002 Chris founded Tilted Mill Entertainment, an independent game development studio in Massachusetts, specializing in city-building strategy games.

Pingback: Perceptive Podcast : A Humble Loot Hunt for City Builders | Game Wisdom()

Pingback: Walkers in City Builders « Kynosarges()

Pingback: Perceptive Podcast: More Fun at EA's Expense | Game Wisdom()

Pingback: Socializing Game Design | Game Wisdom()

Pingback: Walkers in City Builders | Kynosarges Weblog()